It’s surprisingly hard to find anything about the Bunyip among the usual cryptid documentaries. The Yowie gets its time in the figurative sun. The Bunyip is the province of much more obscure sources, mostly Youtube videos and shorts. There is a brief segment in the PBS series, Monstrum, but that’s basically it.

The PBS segment, which first aired in 2020, sums it up as a multifaceted legend among the Aboriginal peoples in and around Victoria in Australia. It’s a water spirit and a cautionary tale, and its nature and appearance vary widely depending on who is telling the story.

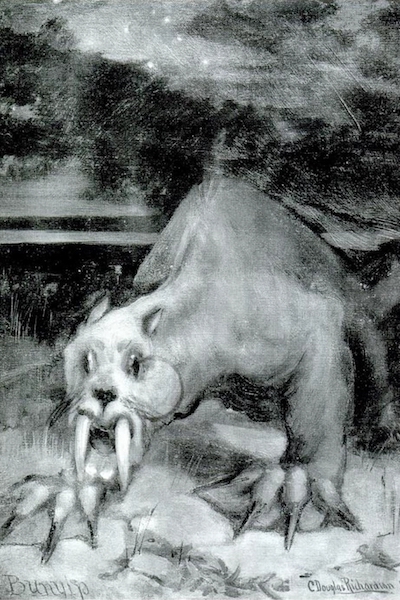

The word bunyip or banib according to this episode means “amphibious spirit-being.” It’s also been called Tanutbun, Mulyawonk, Mulgyewonk, and Katenpai. In some stories it resembles a seal, in others it’s more of a chimera of emu, horse, kangaroo, or alligator. It may have long and shaggy hair, or feathers, or scales.

One distinctive and fairly consistent trait is its loud, booming voice. The sound can actually make a person ill. The creature may have sorcerous powers as well, and the ability to lure its victims into its clutches.

Dr. Emily Zorka, the host of the episode, points out that the wide variety of stories has kept the legend alive. There’s no single story because there’s no single group of indigenous peoples. Before the arrival of European colonizers, there were over 250 languages and many different cultures spread across the continent.

The one thing all the stories have in common is their function as a warning. Inland waters are dangerous. Humans of all ages must respect the water. It’s unpredictable. It can swallow you alive.

Often the bunyip is nocturnal. Humans who go down to the water at night may be attacked and wounded. They may even be hauled away to the bunyip’s lair.

The first colonizers, hearing the stories, believed they must refer to real animals. As Dr. Zorka points out, Australian fauna were absolutely weird by European standards. A vicious water monster with a loud voice was no stranger than anything else they happened across.

There were waves of sightings; there were naturalists hunting for physical evidence. Fossils of megafauna added a new dimension to the story. There were, inevitably, misidentifications and, equally inevitably, hoaxes. Those proliferated to the point that the word bunyip actually came to mean a hoax or a tall tale.

The episode leans slightly toward the idea that some of the legends might refer to dugongs, a manatee-like sea mammal that might conceivably have wandered up rivers into inland waters. It doesn’t commit; it’s more focused on the breadth of indigenous tradition, and the spiritual and cultural significance of the creature.

Of the many other shorts and the few slightly longer videos, the one I found most useful was by someone called A Crowing Cockatrice and titled Bunyip—The Monster That Could Be Anything. It aired around 2023, and it addresses most of the usual subjects including the various names, the indigenous stories, and the history of the cryptid since the arrival of European colonizers.

It talks about the various descriptions, discusses the possible real-world origins of the stories, and, at the end, branches off into outright speculative fiction. Start with a likely ancient species, say a proto-seal, address the issues of food sources and habitat, and extrapolate from that. How would the proto-seal evolve to suit its environment? What traits would it have to develop in order to fit the stories?

Which is fun as worldbuilding, but it’s fairly up front about not being meant to describe a real animal. It’s a thought experiment.

What leads up to it, however, is a pretty thorough examination of the existing stories. The basic animal is a large mammal with shaggy dark brown or black fur, a head like a dog or a horse, flippers like a seal, and tusks. Sometimes it has a long, swan-like neck with a flowing mane. It inhabits rivers, lakes, and the backwaters called billabongs, and it’s usually malevolent. It will attack and eat people. And it has a terrible, deafening, booming voice.

Some less common descriptions tell of a beast four times the size of a large dog, with greyish or white hair, four hooves, a stump of a tail, huge teeth, and tusks like a boar. Or it has a head like an emu with a long, serrated beak, a body like an alligator. It’s four-legged and swims like a frog, but is able to walk on two legs on land; it kills by hugging its prey. Or it’s about a meter long, with a head like a bulldog, and front flippers like a bat’s wings.

It’s infinitely mutable, and changes from place to place and from story to story. The dog-headed version might be based on sightings of seals sighted far inland from the sea. The huge shaggy four-legged version could be an ancient memory of megafauna that that went extinct after humans first came to Australia. The booming voice could belong to a brown bittern, an elusive bird with a very loud cry.

One variant is a marine creature, supposedly sighted by colonists around Port Philip in the 1800s. It was called the Tuntapan: emu-headed, with a long, maned neck and flippers, and a taste for human flesh. Mostly however it lived on crayfish, and it laid exactly two eggs. (Our host does not speculate as to how witnesses confirmed this fact.) Another version seems to have been conflated with the Yowie: half human, half fish, with a mat of reeds on its head.

I particularly like the suggestion that some of the sightings might have been swagmen: humans on the run from the law. They were so named for their huge rucksacks, which gave them a monstrous, misshapen look, especially at night. If they were pursued, supposedly they would take to the water. When the pursuers had gone on by, they emerged covered in mud and weeds, making strange and terrifying noises to scare off anyone who might be spying on them. That would be straightforward exploitation of the myth to save themselves from capture—a reversal of the stories of bunyips hauling humans off to their lairs.

It’s interesting that, for the most part, modern cryptid hunters don’t seem to be looking for this creature; or if they are, they’re not involving the major media. There were hunts in the nineteenth century, often led by scientific types, and numerous sightings to go along with them, but after the first third of the twentieth century, both sightings and scientists dropped off sharply. The Yowie seems to get the bulk of the attention these days, maybe because of its resemblance to the popular Bigfoot/Sasquatch/Yeti.

The bunyip has shrunk in one way, to a joke or a hoax or a children’s story. In another, it’s returned to its ancient origins. It doesn’t need to be a physical animal, though it pleases the Western mind to speculate as to what might be. It’s enough for it to be a creature of myth and dream, a spirit that guarded the waters long before the first Europeans invaded its world.