In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

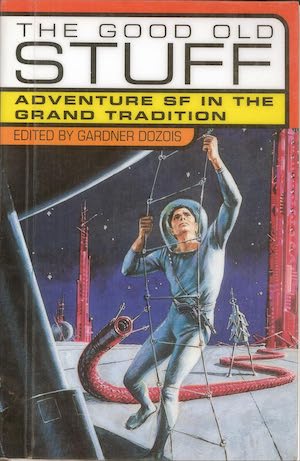

Today we’re looking at a collection, The Good Old Stuff, with a theme that’s quite similar to the charter for this column: “Adventure SF in the Grand Tradition.” The book is edited by Gardner Dozois, whose impeccable taste always produced collections full of enjoyable reading. The copy of the book I am using for this review is a trade paperback published by St. Martin’s Griffin in 1998, loaned to me by my son (there are advantages to being in a multi-generational family of fans). The book, which includes stories from the end of World War II to the mid-1970s, encompasses science fiction adventures in a number of different forms, including space opera, planetary romance, and a time travel tale (there is also a companion volume, The Good New Stuff, which covers work from the late 1970s to late 1990s, which I might visit in a future column). I don’t have room to provide biographical information on all the authors, but many stories have a link to my previous reviews of their work.

The reason I’ve picked a book that overlaps so closely with the stated theme of this column is to recognize an anniversary: This review is my 200th to appear on Reactor under the “Front Lines and Frontiers” banner. The column started over eight years ago, in February 2016. After appearing monthly for about a year and a half, it went to a bi-weekly schedule. It has been a joy to create. After all, what old timer doesn’t love the opportunity to talk about favorite books, and reminisce about experiences in science fiction fandom? I’d like to take this opportunity to thank the folks at Reactor for sponsoring and supporting my efforts, and all the readers who have followed the reviews and chimed in to discuss them over the years.

About the Editor

Gardner Dozois (1947-2018) was a noted American science fiction editor and author. He edited Asimov’s Science Fiction magazine from 1984 to 2004. He created the anthology series The Year’s Best Science Fiction in 1984, and edited the annual collections until his death. Dozois also edited dozens of themed anthologies with a variety of collaborators over the years. He won fifteen Hugo awards for his editing work, and two Nebula awards for short stories. I previously reviewed his collections Old Mars and Old Venus here.

The Good Old Stuff

The book opens with a preface from the editor, who also provided introductions to each of the stories. Dozois always provides interesting historical context and observations on the stories, and these contributions remain a highlight of his collections.

The first story is “The Rull” by A.E. van Vogt. This one was new to me, but like many other van Vogt stories, has a surrealistic air. Two scout ships crash on a high plateau on a contested planet, and the single survivors on each struggle to control each other’s mind. The idea of two warriors continuing the fight after all their comrades are dead is not a new one, but van Vogt gave it a science fictional twist and a clever ending. (Read more on van Vogt here.)

“The Second Night of Summer,” by James H. Schmitz, is one of my favorite stories of all time. Young Grimp is excited that the start of summer will bring one of his favorite people, the traveling medicine salesperson Grandma Wannattel, to his village, in her wagon drawn by a “pony” that resembles a rhino more than a horse. What Grimp doesn’t know is that the planet Noorhut is threatened by invaders from another dimension, that Grandma is an undercover agent whose task is to keep them from breaking through, and that if she fails, the Space Navy must destroy the planet to contain the aliens. Schmitz does an excellent job of balancing the lighthearted local issues with the weighty matter of planetary survival, keeping the reader on edge until the end. Schmitz did more to bring female protagonists into science fiction than just about anyone in his era, and in this tale, goes one step further by featuring an elderly woman in the role of a planet-saving hero. (Read find more on Schmitz here.)

L. Sprague de Camp gives us “The Galton Whistle,” the tale of an Earthman, Mongkut, on a faraway planet who wants to rule as emperor over the centaur-like inhabitants. Mongkut uses the high-pitched whistle of the title to issue commands to his minions, and enlists another Earthman, Frome, to assist him in building weapons. But Frome does not support Mongkut’s ambitions, which includes forcing marriage on a female missionary from Earth; he figures a way to counteract the whistle and escapes. It is an interesting tale, well told, with a nice twist at the end. (Read more on de Camp here.)

“The New Prime,” by Jack Vance, starts out as a seemly disconnected series of vignettes set on different worlds. Vance was a master of evocative descriptions, but while each of the worlds is richly imagined, I began to get confused. Then the story reveals that these are telepathic tests, given to people who might be chosen to replace the ruler of humanity, the Galactic Prime. The Prime receives the highest score and argues his rule should continue, but others point out that a test he himself designed will naturally favor his personality. Their idea of what leader would be best for humanity, however, left me scratching my head.

A young trader named Alen finds himself promoted to Journeyman in “That Share of Glory” by C.M. Kornbluth. In his first voyage, he deals skillfully with alien tax collectors, and in trading the goods his ship carries. And then he faces an even more challenging situation when a crewman is arrested by local authorities. In the end, he is humbled by finding being a Journeyman is not the end of his training. (Read more on Kornbluth here.)

Leigh Brackett, a master of planetary romance, provides the evocative tale “The Last Days of Shandakor.” Set on a Mars that’s in decline, it follows a researcher from Earth who wants to explore the dying city of Shandakor. He finds the city filled with projected images of bustling citizens created by a mysterious machine, with that ghostly population the only thing keeping hill people from plundering the city. He falls in love with one of the few remaining inhabitants, destroys the machine in an attempt to save her from doom, but is horrified by what ensues. (Read more on Brackett here.)

Another of my old favorites is Murray Leinster’s “Exploration Team.” An unauthorized explorer, Huyghens, is on a planet inhabited by hordes of sphexes, vicious creatures who swarm anything that challenges them. He is accompanied by a camera-toting eagle and a family of genetically enhanced Kodiak bears. Huyghens receives a landing request, and is horrified to find it is a Colonial Survey officer, Roane. Roane is looking for a colony that had planned to use robots to carve out an area for its inhabitants underground, and immediately places Huyghens under arrest. They suspect the robot colony was overrun by sphexes, which is why Roane can’t locate it. When they discover that there might be survivors, the two must form an unlikely alliance. The story, a parable about the dangers of living apart from nature rather than within it, with a strong dose of libertarian philosophy, left a powerful impression on me. (Read more on Leinster here).

“The Sky People,” by Poul Anderson, was new to me. It is set on an Earth recovering from a global war, with Māori explorers calling on a South American city just as it is attacked by blimps from the West of what used to be the United States. Anderson does a masterful job creating a post-apocalyptic world and describing war under sail at sea, although I was not convinced by his theory that sail-propelled blimps could be a viable form of transport. The Māori leader is able to defeat the sky invaders, but finds himself torn between affection toward a local noblewoman and his duty to ally his nation with those who possess the technology needed to rebuild the ruined world. (Read more on Anderson here.)

The improbable title of “The Man in the Mailbag,” by Gordon R. Dickson, turns out to be an accurate description of the story’s premise. The gigantic inhabitants of the planet Dilbia have kidnapped an Earth woman, and the man sent to rescue her is transported by strapping him to a local mailman. The situation turns out to be a test to determine whether the locals are willing to accept the visitors from Earth as equals under the law. (Read more on Dickson here.)

I’d heard of the story “Mother Hitton’s Littul Kittons,” by Cordwainer Smith, but before picking up this collection, had not been able to find it. The story is set on the planet of Norstrilia, whose gigantic sheep produce an extract that can extend human life, making its people rich beyond their wildest dreams. Naturally, they need to defend their planet, which they do in a most unusual way. And when an amoral murderer tries to discover their secret, he gets his just deserts by way of the creatures of the story’s title. Smith’s stories are full of improbable situations and characters, but succeed by evoking the same emotions as myth and fairy tales. (Read more on Smith here.)

Every collection has a story I enjoy least, and in this case, it is “A Kind of Artistry” by Brian W. Aldiss. After a strained goodbye to a hypercritical spouse, the story begins with promise, as an explorer is sent to examine, and collect a sample from, an asteroid-sized creature nicknamed the Cliff. But the story then turns to more mundane issues, as he struggles with the fame he earns as a result of his accomplishment, and in the end, the moral of this depressing story seems to be that explorers are motivated to go out adventuring by dislike for their spouses.

I’ll never forget “Gunpowder God” by H. Beam Piper, one of the first science fiction stories I ever read. The cover of Analog that month featured a John Schoenherr painting of a Pennsylvania State Policeman on horseback, improbably surrounded by warriors from the 16th century. That policeman, Calvin Morrison, is accidentally transported to an alternate world by a visiting time machine’s malfunction—a world where scientific advances are suppressed and the secret of making gunpowder hoarded by the cruel priests of Styphon. Morrison’s knowledge of military strategy from throughout history, as well as the recipe for gunpowder, drops him into a series of military adventures, and he becomes a catalyst for disruption of the stagnant society. This story, grounded in some excellent worldbuilding and a large dose of wish fulfilment, captivated my young imagination. (Read more on Piper here.)

“Semley’s Necklace,” by Ursula K. Le Guin, is a sweet and sentimental tale of a young woman who sets out to recover a precious necklace lost by her family generations ago. It has the feel of a fairy tale, as her planet has inhabitants resembling the fae and dwarves of legend. The dwarves have advanced technology shared by visitors from other worlds that allow her to complete her quest, but she pays a steep price for her victory.

In “Moon Duel” by Fritz Leiber, an explorer struggles to survive on Earth’s moon, which is used as a dumping ground for undesirables from a variety of alien races. The premise seems preposterous, but makes for a gripping tale of survival. Moreover, the story ends with a clever little science fictional twist. (Read more on Leiber here.)

Roger Zelazny’s “The Doors of His Face, The Lamps of His Mouth” is set on a habitable Venus, and written just before planetary probes showed us a quite different environment. Zelazny, as he often does, tells the tale in a crisp first-person voice, evoking the feel of old detective novels. The narrator is a broken man, Carl, who is hired by a former lover, Jean Luharich, to pursue the ultimate prize, the massive “Ikky” of the dark seas of Venus (I assume this creature is somehow related to Earth’s extinct ichthyosaurus). Carl has fished for creatures in the seas of two planets, and has been involved in previous failed attempts to land an Ikky. During the last attempt, Carl froze up just when it was time to inject the creature with a sedative that would allow its capture, and he has been haunted by that failure ever since. They set out in a huge ship called Tensquare, built expressly for this purpose, and begin their search. Carl and Jean clash, but it is clear to the other characters, and the reader, that there is still an attraction between them. This excellent tale evokes the end of an era, which fits its place as one of the last of the old-style planetary romances. (Read more on Zelazny here.)

The last story in the collection, “Mother in the Sky with Diamonds,” by James Tiptree, Jr., is a gritty, dark tale set in the Asteroid Belt. It is from the end of the era Dozois chose for the collection, and as he points out in the introduction to the story, its tone is a precursor to the cyberpunk era and the work of authors like Bruce Sterling. Space Safety Inspector Gollem is an old-timer, a relic from an era when the Belt was first being exploited. Corporations dominate the society, and there are criminals who are growing mutant “phages” (I assume that refers to bacteriophages) for some use I don’t think is explained, but must be financially lucrative. These phages sometimes spread out of control and are a threat to their growers, and anyone who visits their ships. Gollem has a sentimental attachment to an old woman, Topanga, who lives in an old abandoned derelict spaceship. She has dementia, but refuses to go for treatment, afraid of losing what little independence she still has. They have an encounter with phagers which goes terribly wrong. The story pulls the reader in, and refuses to let them go until the final sentence.

Final Thoughts

The Good Old Stuff is a great collection that features some of the best adventure stories in science fiction from the middle of the 20th century. Anyone who might want an introduction to stories from that era will find the book to be an excellent starting point. Whenever a reader picks up a collection edited by Gardner Dozois, they are in good hands.

I’m looking forward to hearing from you regarding this particular collection, or any of the authors and stories it features.