Sometimes a writer sets out with a clear thesis that the story is intended to support… and sometimes the reader sets down the resulting book (or, in the case of movies and TV, the viewer looks up from the screen) having come to entirely different conclusions. Let’s look at five examples…

Tomorrow! by Philip Wylie (1954)

Faced with possibility of nuclear attack from those dastardly Reds, twin cities Green Prairie, Missouri, and River City, Kansas opt for very different strategies. Green Prairie embraces civil defense and regular drills, while River City collectively shrugs its shoulders and hopes war never comes.

River City saves time and expense, and avoids inconveniencing local dowager oligarch Minerva Sloan. Green Prairie suffers less and recovers faster from the inevitable Communist attack. In the short run, River City’s inhabitants were free to carry on as though the Cold War was someone else’s problem. In the long run, Green Prairie had a long run.

Wylie’s intention was to convince people that civil defense was worth the trouble. However, not only is it clear that survival requires both preparation and luck, the Soviet’s hilariously miniscule attack—five H‑bombs and twenty-five atomic bombs—is sufficient to kill twenty million Americans, reduce a considerable fraction of the rest of US to chaos, and very nearly force the US to surrender. The actual moral of the novel appears to be that even a very small nuclear war would be hellish and one of any reasonable size would probably render civil defense efforts moot.

Note: While Wylie’s River City certainly does have trouble, it is not the same River City featured in The Music Man (that one’s famously in Iowa), and the status of pool halls is left unclear.

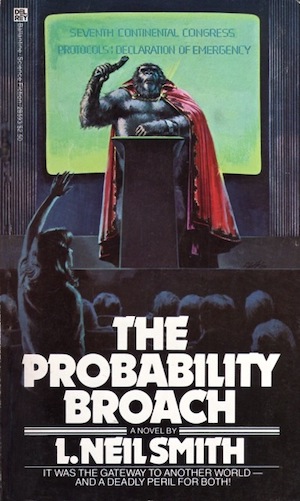

The Probability Broach by L. Neil Smith (1980)

Denver cop Win Bear has the bad luck to live in an increasingly authoritarian United States of America. This becomes personally relevant to Bear when what seems to be an unremarkable murder case places Bear in the crosshairs of the Federal Security Police. Just as well for Bear that his investigation inadvertently catapults him from his home timeline to a very different America.

The North American Confederacy is a libertarian paradise. All intelligent beings—not just the humans—are freed, technology is unbounded by nanny state regulations and basic physical plausibility, and the economy is roaring! And unless Bear can somehow prevent it, the North American Confederacy is doomed from within and without by malevolent federalists!

Presumably the point here was by contrasting the NAC with Bear’s USA to show how superior libertarianism (or as the book puts it, “propertarianism”) is to socialist mixed market states. I could not help but notice that not only does everyone in the NAC perceive themselves to be in a perpetual stage of siege that requires them to be heavily armed at all times, the events of the novel suggest they are correct in this perception. It’s almost as if, to quote a noted sage, libertarianism makes everything worse.

Starship Troopers by Robert A. Heinlein (1959)

Incurious teen dullard Juan Rico1 signs up for military service, less because of any dedication to humanity and more because Carmen Ibañez, with whom Juan is somewhat smitten, signs up. As luck would have it, war breaks out and what should have been a two-year tour of duty becomes a long-term commitment.

This twist of fate proves Juan’s making. Whether he would have continued to drift through life as a civilian is unclear. As a soldier, he is forced to take note of the world around him. Furthermore, he proves well-suited for life in the Terran military, defending humanity against its relentless alien enemies.

I cannot help but notice that the book opens with Juan committing egregious war crimes against the Skinnies. Furthermore, while we never get a Bug’s-eye perspective on things, the fact that the heavily armed humans firmly believe that “[e]ither we spread and wipe out the Bugs, or they spread and wipe us out,” seems legitimate grounds for the Bugs, who seem perfectly capable of coexisting with the Skinnies, to be very concerned about humans. An “Are we the baddies?” moment from Juan would not have been that surprising.

Terminator: The Sarah Connor Chronicles created by Josh Friedman (2008 to 2009)

Terminator II: Judgement Day’s victory proves illusionary. Skynet will still be created, the AI will still turn on humans, billions will still perish, and the long struggle between the human remnant will still end in Skynet’s destruction. The only thing that changed was the timing of Skynet’s creation.

Throughout the two-season series, time travelers—robot and human—arrive in the late 20th and early 21st century, determined to shape history by aiding, impeding, or even killing future resistance leader John Connor. Events make it clear that history is mutable. Is it mutable enough to matter?

Perhaps it was simply due to the need to keep the franchise viable, but every development in the TV series points to time wars being a colossal waste of, well, time. I suspect Terminator’s causality does not permit causeless phenomena, so while it is possible to shuffle timing and players somewhat, it is impossible for a time traveler to eliminate the event that inspired them to travel to the past to try to change history2.

Star Trek: The Original Series created by Gene Roddenberry, et al. (1966–1969)

Star Trek depicted the Starship Enterprise’s five-year mission to explore strange new worlds; to seek out new life and new civilizations; to boldly go where no man has gone before. Additionally, the Enterprise helped preserve the balance of power between its own Federation and the expansionist Klingons, not to mention the Romulans, and where appropriate, intervened in local crises beyond the ability of planetary governments to manage.

All of the above was supposed to be laudable. The Federation are the good guys, the Klingons and Romulans are the antagonists, exploration is always worthwhile, and who doesn’t appreciate a helping hand? The series was an expression of Federation benevolence, conducted at considerable cost in material and red-shirt lives.

Watching the old shows, one cannot help but be struck by the frequency with which Star Fleet personnel, if not closely supervised, hare off on ill-advised quests for immortality, accidentally gangsterize whole planets, or install fascist governments in the belief that these are efficient. As well, the region immediately around the Federation is richly stocked with godlike entities best left uncontacted. It may not be a coincidence that the oldest civilizations in the region eschew interstellar travel, and all of the expansionist cultures are also young, and presumably unaware of the inherent hazards of exploration. It may well be ill-advised to send an unsupervised Kirk off to see how many gods he can contact before he inadvertently dooms us all.

These are just a few of the works I have finished reading or watching and found myself having arrived at a destination other than the one the author or creator likely intended. Am I alone in this? Do you have better examples?