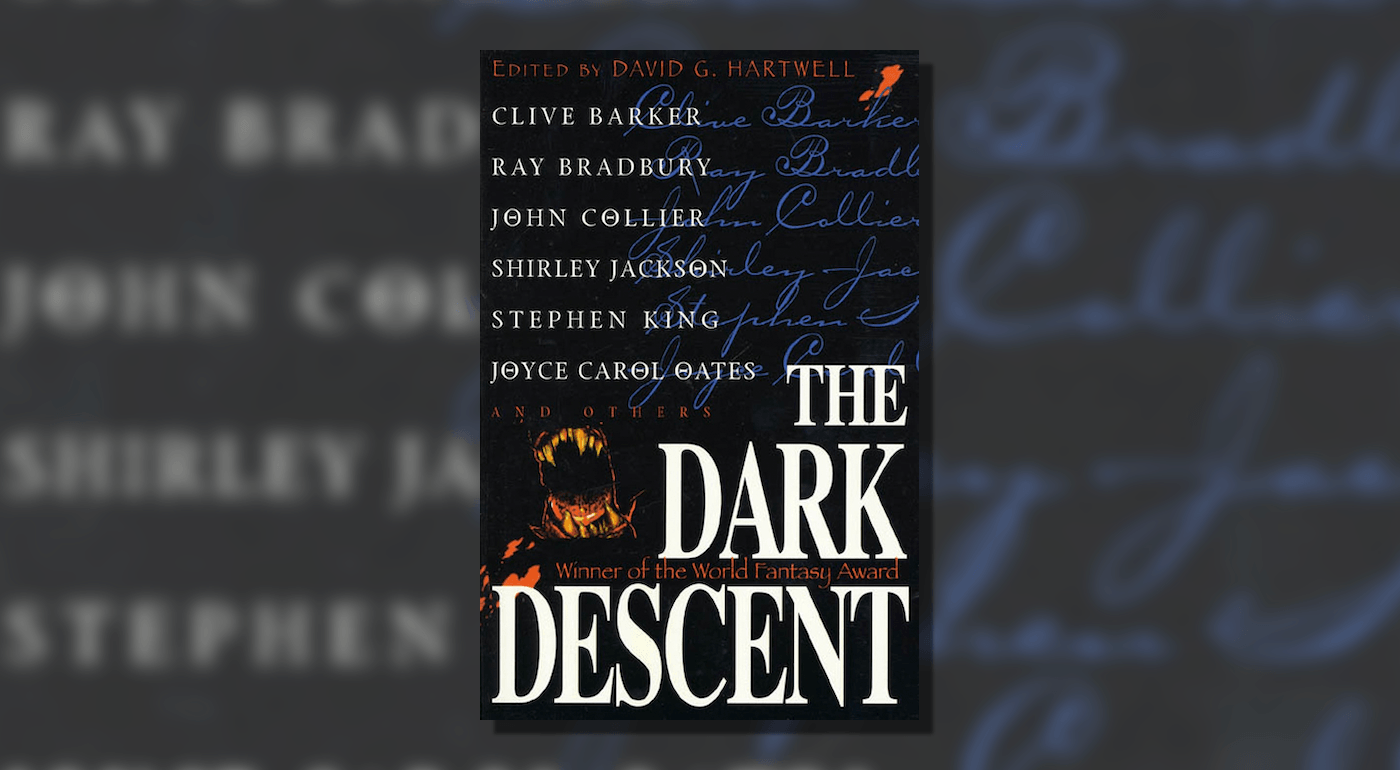

Welcome back to Dissecting The Dark Descent, where we lovingly delve into the guts of David Hartwell’s seminal 1987 anthology story by story, and in the process, explore the underpinnings of a genre we all love. For an in-depth introduction, here’s the intro post.

David Hartwell’s introduction to this story calls Ramsey Campbell “one of horror’s greatest stylists,” and it’s difficult to disagree with (especially given that he’s commented on these articles in the past). Starting out in a more Lovecraftian vein of cosmic horror, Campbell developed his own deeply unnerving style that took the existing strain of cosmic horror and combined it with a sense of place gained from his surroundings, bringing in elements of folk horror, gothic horror, social drama, modern settings, and suburban gothic to rival King. “Mackintosh Willy” is a strong example of this synthesis, using the basic components of a gothic ghost story—a sinister haunted location, a local legend, repressed trauma and fear, obsession, and two twisted acts driven by these emotions—to craft a suburban gothic horror story that reminds the reader that what’s left unexplained and unrevealed is sometimes more important than what’s laid out in perfect detail on the page.

The red brick shelter by the reflecting pool in Newsham Park is home to Mackintosh Willy, a local transient who curls up in the corner at twilight and chases the local children when they get too close to his territory. Nothing is known about Willy beyond that, as even the name given to him is taken from the graffiti in his shelter. Over time, he becomes a local legend, a test of courage for the boys in the neighborhood where he lays his head. When Willy is discovered dead and his corpse is later desecrated (possibly by a young man named Mark), his legend only grows over the years, with his terrifying, obsessive presence haunting both the shelter and Mark. For while Willy’s mortal life might have ended on one rainy summer day, both his status as a local monster and his revenge on Mark are only just beginning.

It isn’t that the central terror of “Mackintosh Willy” is unexplained that makes it so horrifying, but rather that the explanation is organic. Suburbia (or in this case, the quasi-suburbia beyond the city center of Liverpool) isn’t a place of well-defined explanations or legends, something that makes many suburban gothic stories (as modern ones have a tendency to lean on exposition) an exercise in frustration. People don’t like to talk about the unpleasant events that go on around them, especially around adolescents, who make up the central cast of Campbell’s story. There are a half-dozen things Willy could be, from a subconscious manifestation of the kids’ fears of unhoused people living in the pond shelter to a revenant specter, but none of them are really confirmed. It’s not even fully confirmed what happened between Mark and Willy’s corpse—Mark apparently did something awful, possibly involving putting out Willy’s eyes (although it’s never fully clear what happened, and the narrative only hints at who was responsible). Nothing is directly spelled out other than Willy’s death, his haunting the park shelter, and whatever Mark did having a significant impact on both Mark himself and the legend surrounding Willy. It allows the imagination to fill in the blanks around Mark and Willy, with the legends surrounding them growing stronger with each retelling. Traumatic or disturbing events in suburbs and small towns are often left unmentioned or shrouded in shadow, their legend only growing with time; whatever horrible things happened around Willy and Mark are too terrible to talk about, and the repression creates an unnerving mystery, ending in Willy’s revenant haunting the shelter at the park.

With so much of the story left a mystery, it’s hard to fully see Mark as deserving of the hideous fate visited upon him. Mark doesn’t seem at any point like a bad person. If anything, when he leaves the neighborhood gang, they immediately turn to shoplifting and get caught immediately. Mark is even described as generous, although standoffish and deathly afraid of Willy’s shelter. When pushed to examine it or go near it, Mark reacts the way a trauma survivor would as much as he does out of guilt or fear. Ben’s insistence that “Willy used to chase Mark around and around the pool,” with Mark lashing out verbally when Ben recalls the memory feels less like embarrassment at cowardice, and more like Ben was deliberately poking a raw nerve, especially if Mark had become upset enough by Willy “chasing” him to do something that clearly left him both terrified of the shelter where Willy’s ghost resides and horrified at what he’d done. The savagery of Mark’s desecration also points towards some form of trauma, as it’s only after Willy finally dies that Mark feels confident enough to approach him—at which point he assaults the corpse, putting out Willy’s eyes and covering them with bottle caps, as if trying to conquer his fear and trauma once and for all. There’s also the slightest insinuation of homophobia, as if Willy singled out Mark to chase specifically because of a feeling he had about the boy, or something Mark might have felt about Willy, coupled with the brutal way Mark finally desecrates Willy’s body.

The obsession angle also feeds back into the legend of Willy. His power over Mark and the complete omission of details surrounding his death make him seem even more shadowy than when he was a “creature of the night” who chased boys who ventured too close to his shelter. There’s even a sinister aspect to his legend that grows after his death, with the graffiti on the shelter referencing his death and desecration, and his corner of the shelter being shadowed in perpetual darkness. Most of his posthumous mumblings also have to do with his ocular trauma, as if that binds him to both the boy who discovered his body and the boy who mutilated his corpse. As his legend grows, the shelter by the pool becomes more and more unnerving, growing from a curiosity to the locus for a tangled knot of legends surrounding his death, Mark’s trauma, and the eventual collision of the two in Mark’s own drowning by Willy’s ghost. Even after the narrator moves away, the shelter still exerts a hold on him when he visits home for the holidays, Willy’s power still very much in play.

What makes a “Mackintosh Willy” a great suburban gothic ghost story is the convergence of these things—the lack of details and exposition due to the suppression of things That Just Aren’t Talked About, the repression of Mark’s emotions as he refuses to admit what happened to him, the already legendary status of Willy as a “creature of the night” haunting the shelter before his death, the unresolved trauma, and the ultimate demise of Mark all grow the power of the revenant shade in the shelter. Even the narration itself plays into this, as it’s a recollection of a young man who grew up in the same town and has his own thoughts on the local legends and events around him. That shadowy, semi-nostalgic memory of Willy’s haunted shelter and the mystery surrounding its occupant in life and death invites the reader’s imagination to try to sketch in the details and fill in the disturbing blanks. It’s in those blanks where the true power and horror of this story resides.

And now to turn it over to you: Does the lack of exposition aid or hinder the horror in “Mackintosh Willy”? What really happened—did Mark actually murder Willy, or did he lash out and desecrate his corpse? Am I gonna get roasted in my own comments thread by the author of the short story?

And please join us in two weeks as we explore “The Jolly Corner,” a classic work of psychological horror by the legendary Henry James.