As a health care writer and patient advocate for over 27 years, I have interacted with thousands of patients who experience chronic severe pain, caregivers who support struggling family members, and clinicians who treat painful conditions. Depression and anxiety are very common in these patients and may significantly complicate treatment. Untreated depression – or under-treated pain – can cause increases in healing times, suicidal ideation, and even suicide itself.

On the other hand, we know patients’ expectations that a treatment will help them and may improve some patients’ symptoms even when they are given an inert sugar pill (“placebo effect”). Positive doctor-patient relationships and mutual respect tend to promote better outcomes. Negative relationships are associated with worse outcomes (“nocebo effect”).

Interactions of the human psyche and soma (mind versus body) are a subject of controversy between lay people and clinical professionals. Among pain patients and their health care providers, an important question is, “Does pain cause depression, or is it the other way around?” By extension, “Can pain be reduced by also treating depression or anxiety?” Finally, “Do childhood adverse experiences or emotional trauma cause physical pain in adult life?”

I have found over the decades of my public advocacy that answers to these questions tend to amount to “sometimes for some people …” There is no one-size-fits-all “holistic” therapy for either pain or depression. We’re still learning.

That being said, psychosomatic medicine has come to be recognized in recent years as having a degree of positive validity even while the medical evidence is mixed. High levels of stress and emotional upset clearly influence physical symptoms and cause observable neurological changes. Sustained high levels of pain may cause sleep disturbances and disrupt family relationships, promoting both chronic depression and higher levels of pain in a spiral of negative effects.

Treatment of pain and depression is complicated by inadequacies in doctor training. One survey of medical school curricula found that the average medical student is exposed to only nine hours of instruction on diagnosis and treatment of pain. Expansion of this exposure must wait for rotations during internship or fellowship programs. And even there, much of what doctors learn about pain, depression, and the risk of painkiller addiction will need to be unlearned later in clinical practice.

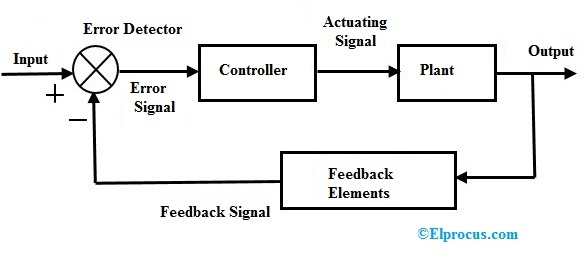

I propose that a concept from engineering may offer doctors an organizing framework for better understanding many questions about integrated treatment of pain, depression, and anxiety. This concept is one of “closed-loop control systems.” The mathematics underpinning the concept dates from the late 1860s. Few clinicians are deeply exposed to this approach, though many engineers will immediately recognize it.

In health care systems, the “input” to the system is a multi-element program of therapy intended to treat a disease, disorder, or symptom. The plant” is the mind and body of the patient. “Outputs” are the results of treatment.

What is unique in this concept is the “controller,” the “feedback elements,” and the fact that these elements directly influence the results of treatment in ways that few doctors are taught to recognize. Medical school education, for the most part, addresses only the right-facing arrows in this diagram and often neglects details of the controller block.

The “controller” in pain treatment is a kind of “translator.” For pharmacological treatments, the controller metabolizes pharmaceutical chemicals into simpler sub-components that cross the blood-brain barrier to reach the pain processing centers of the brain. Metabolism also transforms treatments into physical effects felt not only in nerves or the brain but also in hormones, organs, and soft tissues.

A program of psychosomatic medicine or psychological therapy might also pass through its own translator to produce effects in “the plant” (mind, body, or both).

“Feedback elements” are multi-dimensiona,l and observations of the doctor and patient are major components. Is the treatment working? Has the patient’s level of pain or quality of life improved? If treatment isn’t working, what else can be tried?

The transfer relationships of the controller and plant are not constant. These functions change both in response to treatment and independently due to the life experiences of the patient and doctor. Some elements of both controller and plant may not be observable; we can only guess what they are and how they operate. Arguably, the best outcomes of both patient-centered medicine and evidence-based medicine are realized when all parties embrace these elements.

Note to doctors: hang in here with us. This is complex reading, but there really is a bottom line to the discussion.

To return to the diagram: It cannot be overemphasized that patients themselves are often highly accurate observers of their own outcomes. What they observe is “fed back” as information to doctors or in their willingness to comply with clinician proposals. Even when the patient is mistaken in their observations, a few questions by the clinician may clarify what is going on. And incidentally, the term “non-compliant” should be avoided at all costs in patient records. It can be a “kiss of death” for effective treatment.

For clinicians, what this means is that you must listen and accord credibility to what the patient says. You can assist them in articulating what they are experiencing. But you discount or distrust their observations to your own and their peril.

When a patient tells us that a past treatment for their pain has been effective — or ineffective — then we need to respect their input unless there is evidence that they misunderstand or are misrepresenting what they experience. When a patient tells us that they are very depressed or anxious, then we need to treat those symptoms aggressively and monitor the patient’s progress not only for pain but also for depression.

Pain and depression are not “fire and forget” targets. Both require ongoing management.

I offer a final thought from my own interactions with patients and caregivers. In 27 years, I have never heard a patient say that their pain was “caused” by their own mental attitude or by early childhood emotional traumas. Even when such factors exist, they do not “cause” pain (although, in some patients, early traumas may complicate later treatment). By contrast, I have many times heard that the refusal of a physician to hear and trust their patient has made the patient’s life much worse.

The systems model for medical treatment offers much value, particularly by reminding us to listen to what patients say and to acknowledge them as participants in their own treatments. Systems thinking also informs us that “It’s all in your head” is never an ethically or clinically correct response to pain.

Richard A. Lawhern is a patient advocate.