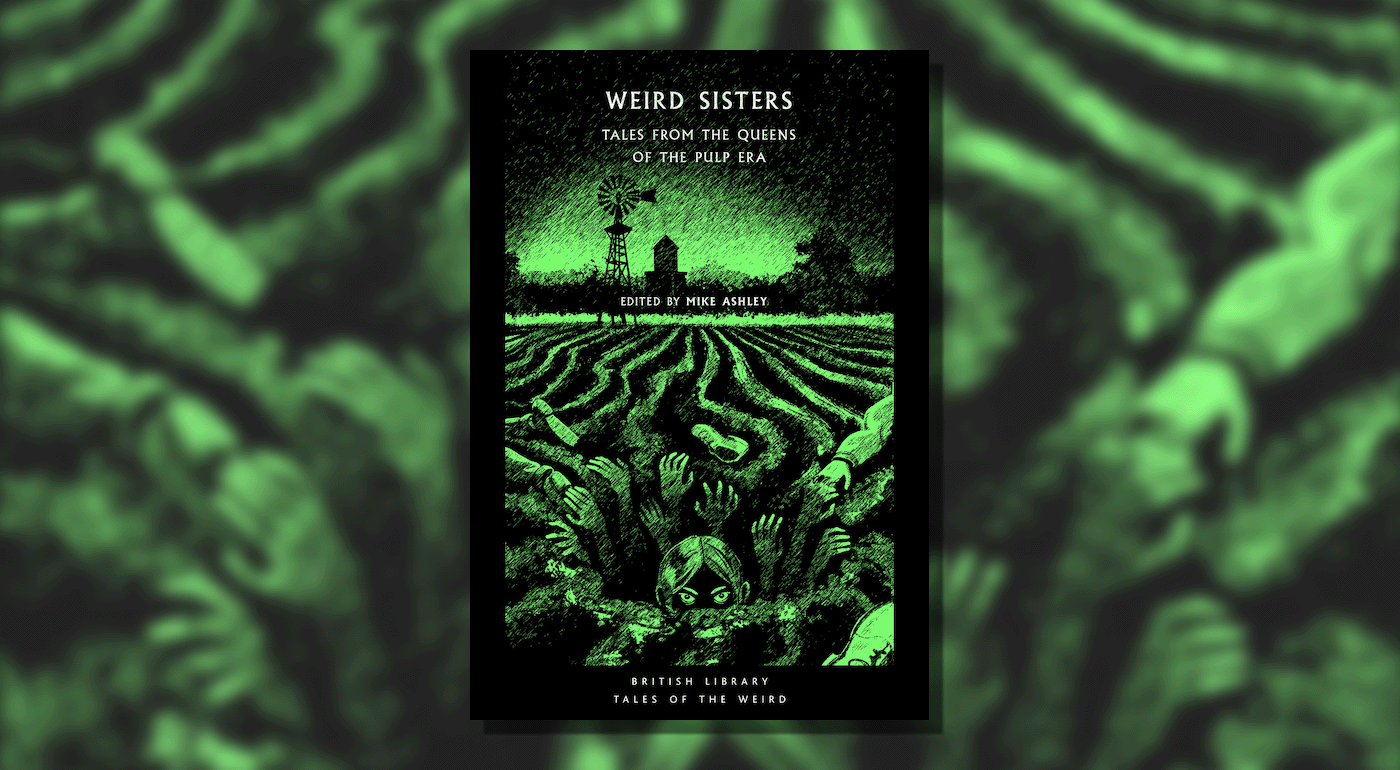

Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches. This week, we cover Mary Elizabeth Counselman’s “Mommy,” first published in the April 1939 issue of Weird Tales. You can find it in Mike Ashley’s Weird Sisters: Tales from the Queens of the Pulp Era. Spoilers ahead!

Mrs. Ellison is a well-to-do childless widow looking to adopt “a wonderful little daughter.” Now, standing in the Acipco County Orphanage yard, she has plenty of choices. On the seesaw is a dark-haired “lovely cherub.” On the swingset is a laughing brown-eyed girl who reminds Ellison of herself. How’s she to make a decision that will change her life and a child’s forever? It feels “inhuman” to be “shopping for a daughter.” If only the child herself had the vision to select her adopter.

A tug makes Ellison look down at a thin girl with “penetrating blue eyes” too large for her “sallow, sensitive face.” Ellison’s never seen a more unattractive child, and yet the girl’s smile is sweet and strange, “full of wistfulness and yet the paradox of a quiet knowledge.” A timid yet compelling voice asks: “Are you the lady my mommy sent for me?”

Ellison asks if the girl’s mommy has “gone to Heaven.” No, the girl answers. Her mommy talks to her every night.

The matron arrives and sends the girl—Martha—away. Her impatient tone surprises Ellison, who watches other children shying away from the girl. Matron explains that Martha’s their “problem child.” A misfit, Ellison supposes. Understandably so if the mother visits but can’t take Martha home.

But no: Martha’s mother died the previous year. Shocked by her loss, Martha’s convinced that her mother’s always beside her, and is surprised others can’t see her. Truth be told, strange things happen around Martha. Her mother, a “dance-hall hostess,” bore Martha out of wedlock. The birth woke “a fierce maternal instinct.” Mother took a mill job, where conditions aggravated her tuberculosis; though she “fought death with a stubborn will that prolonged her life by months,” she finally had to tell Martha she was casting aside her sick body so she could take better care of her. Hence the fixation.

Needled by Ellison’s skepticism, the matron supplies details. Once, an actress arranged to adopt Martha. Martha protested that Mommy hadn’t sent that lady. Last minute, the actress backed out. She’d broken her nose in a fall, leaving her future income uncertain. It turned out that she’d meant to adopt Martha as a publicity stunt, to divert attention from a scandal. Another time, the orphanage’s meager amusement fund had to exclude ten children from attending a circus. Martha, one of the ten, so loudly insisted that Mommy would pay the extra children’s way that the matron reluctantly gave in. As she was buying tickets, a bundle of cash appeared underfoot—just enough to cover the extra children! Then, last fall, Martha swallowed a safety pin. An ice storm prevented getting help, but a bus carrying convention-going physicians broke down in front of the orphanage, and an EENT specialist soon had that safety pin out. Finally, Martha’s always finding pennies, candy, toys, which she says Mommy leads her to. No wonder the other orphans believe Martha’s attended by a ghost! And who’ll want to adopt a “crazy child”?

Ellison wants her, that’s who. What Martha needs to break her delusion is an affectionate home. Though she hopes Ellison won’t regret her sudden decision, the matron agrees to speed the necessary formalities. Ellison then goes to embrace the solitary Martha. Martha feels like “a small bony doll” in her arms. Like a challenge. When Ellison tells Martha she’s to call her Mommy from now on, the girl gravely says she will, if Mommy says it’s all right. Oh, and she so hopes Ellison will be the one Mommy has picked!

Ellison leaves, uncertain whether she’s “won the first match” with her new daughter. A few days later, she dismisses her chauffeur to drive Martha home herself. She’s come with a new silk dress and a terrier puppy who delights Martha, and yet Ellison seethes at the thought of the “selfish hysterical woman” who gave that damaging death-bed promise. She imagines Martha’s first mother sitting between her and Martha in the car. Yet, though she does sense an “alien presence,” it feels like it sits on Martha’s other side, guarding the child in that direction while Ellison guards her in the other. What a strange, superstitious image.

She gives Martha a one-armed hug. Martha snuggles into it, “aglow with happiness,” but she sours the mood by telling Ellison how Mommy said she’d picked Ellison a long time ago. Ellison draws back, stung, and says sternly that Martha must stop pretending Mommy hasn’t gone to Heaven!

Martha screams, but not at the ultimatum. Ellison looks up to see a driverless gas truck barreling down the narrow hill street directly at them. There’s no room to pull out of the way. She urges Martha to jump out of the car and run, but Martha goes on whispering for Mommy to make the truck stop.

As Ellison struggles to drag Martha from the doomed vehicle, the runaway truck lurches sideways, gears stripping, and halts just five feet from them. People rush over, including the truck’s driver. He was sure the truck was braked, but if a packing case hadn’t knocked the gear-shift into reverse at the last minute—

Ellison can only nod. She looks from the truck to Martha, whose strange quiet smile has amazed the onlookers. After a moment, Ellison whispers, “Let you and I and… and Mommy go along home.”

The Degenerate Dutch: Mrs. Ellison thinks of Mommy as a “selfish hysterical woman,” and matron is at pains to talk about her scandalous life prior to Martha’s birth.

Madness Takes Its Toll: The adults really, really don’t want Martha to be right about Mommy. Her mind has been tortured beyond endurance, resulting in a positive fixation. She’s a “crazy child”—why would anyone want her when there are “so many normal ones to be had”?

Anne’s Commentary

Mary Elizabeth Counselman published widely during the decades when fiction and poetry were standard features of general interest magazines—her work appeared not only in genre mags like Weird Tales but in The Saturday Evening Post, Collier’s, Ladies’ Home Journal and Good Housekeeping. I wonder what the readers of LHJ and GH would have made of “Mommy.” The title is innocuous enough, appropriate for an upbeat, nostalgic, even inspirational story. The introductory note to “Mommy” in the Weird Sisters anthology describes it as “moving” and “atmospheric.”

“Moving” and “atmospheric” are adjectives that can cut more than one way, as (for me) does the story itself.

The same note remarks that Counselman’s 1942 story, “Parasite Mansion,” got wider recognition after being adapted for Boris Karloff’s Thriller. Alan Warren’s series guide, This is a Thriller, includes a quote from Counselman about her horror writing philosophy:

“The Hallowe’en scariness of the bumbling but kindly Wizard of Oz has always appealed to me more than the gruesome, morbid fiction of H. P. Lovecraft, Clark Ashton Smith, and those later authors who were influenced by their doom philosophies. My eerie shades bubble with an irrepressible sense of humour, ready to laugh with (never at) those earth-bound mortals whose fears they once shared.”

“Mommy” may not recall HPL or Klarkash-Ton, but there are more facets to Counselman’s creed than are expressed in the paragraph above. Martha’s spectral Mommy is “eerie,” but she’s hardly bubbly, humorous, or sympathetic to the foibles and fears of the living. Martha’s not the one with the pathological fixation. Instead she’s the object of a “maternal instinct” so fierce it has burst the bonds of death. In her life as a dance-hall hostess and millworker, Mommy was the victim. As a ghost, Mommy can be the victimizer, only in the sacred cause of motherhood. Can you blame the tigress for defending her cubs, whether the perceived threat is a predator or an ecotourist bumbling into her den?

Put blame aside, the predator deprived of a meal or the ecotourist of a limb needn’t be happy about it.

Mommy’s routine actions on Martha’s behalf are benign. She steers the girl to small change and treats. She arranges for Martha and the other left-out children to attend a circus, while sparing the matron unwarranted expenditure. She reroutes a bus of MD’s to the orphanage so that the applicable specialist can pluck a safety pin from Martha’s throat. She chats with Martha in the night and promises to pick the right adoptive mother for her. Where’s the harm in any of this?

The harm is in the accumulation of small uncanny events which make the staff and other orphans afraid of Martha, leaving her suspected, resented, isolated, shunned. A larger uncanny event is the accident that makes Martha’s actress adopter cry off. The matron initially regrets Martha’s lost opportunity. Then she learns that the actress only wanted to adopt Martha as a publicity stunt to overshadow her involvement in a looming scandal. Martha’s loss was a lucky escape, but certain aspects of the affair are unnervingly macabre. Why did Martha fight going to the actress and scream that Mommy hadn’t picked her for Martha’s new mother? How weird that the actress took a fall downstairs the morning the adoption would have been finalized, not to break a leg or neck but her nose—a greater calamity for a woman whose career depended on her looks. If Martha’s Mommy was responsible for the fall, wouldn’t that make Mommy seem outright vindictive as well as protective?

The most spectacular of Mommy’s “saves” is her rescue of Martha, and Ellison, from the runaway truck. Or is this instead her most sinister intervention? Mrs. Ellison has been skeptical about Mommy’s existence and intends to cure Martha of her delusion. Even so, she herself visualizes “Mommy” as a ghost to be slain; driving Martha home, she seethes with resentment towards the girl’s birth mother. The metaphoric ghost grows in her own mind toward supernatural reality, a wraith she must exorcise from both her and Martha. But the alien presence she senses in the car sits not like a barrier between her and Martha, but on Martha’s other side, an allied guardian.

Ellison rejects this impression, and when Martha speaks of Mommy choosing Ellison all along, she commands Martha to forget her “nonsense” about Mommy being real. Is it coincidence or consequence that in the next moment the two see the runaway truck? I lean toward consequence—having just extended an olive branch to Ellison, Mommy’s angered by its rejection and decides Ellison needs a harsher lesson. Ever the adept poltergeist, Mommy releases the truck’s brakes. Moments later, when Ellison proves worthy by trying to get Martha to safety before herself, Mommy diverts the truck.

Martha knew Mommy would save them, hence her calmness in the face of certain squashing. Hence her “strange, quiet smile” after the near-miss. She believes Mommy’s earned Ellison’s belief. Sure enough, Ellison’s first words post-scare—post-warning?—is to propose that she and Martha and Mommy go home. Together.

I hope this new extended family will be a happy one for all, including the miraculously yap-free puppy. Maybe it can be, too, as long as Ellison remembers that Martha does have two Mommies, and that one of them can be either a fierce ally or a fiercer opponent.

It’s New-Mommy’s choice.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

With this week’s selection, “surprisingly wholesome weirdness” reaches subgenre status for our column. The twins in “How Fear Departed from the Long Gallery” are dangerous, but like any tantrum-thrower really just need firm parental understanding. Then there’s the gallant limb-returning narrator of “The Mummy’s Foot,” and said foot’s grateful recipient. And now a mostly-benevolent guardian ghost, and a story where the scariest thing is 1930s adoption norms. Which are, admittedly, pretty scary.

I’ve also recently read Adrift in Currents Clean and Clear, the latest in Seanan McGuire’s Wayward Children series. That book primed me to raise my eyebrows hard at adoptive parents too busy with their “virtuous rescuer” scripts to actually notice the kids they’ve got, or upset when kids don’t gratefully comply with said scripts. Thus, I was fully prepared for Mrs. Ellison to pay for her hubris—and for her insistence that she was Martha’s only mother. It would hardly be a surprising fate, for someone who expects a recent orphan to be instantly all hugs.

But of course, this is a time when that attitude was normal—where even acknowledging adoption at all was often worth a side-eye, let alone acknowledging any valid role for birth parents in a kid’s life. It was a time not only of closed adoptions and lying to kids about your genetic relationship, but of second husbands throwing stepkids out on the street as “another man’s children.” The idea that a kid might have two moms and no dad was beyond the pale. One of the moms being dead does not ease the concept.

As someone genetically unrelated to my kids—a childless cat lady by some standards, despite being up late last night snuggling an anxious child with a migraine—I take this kind of thing personally.

I give Doyleist kudos, therefore, to Counselman for favoring of this non-traditional family arrangement, and Watsonian ones to Mrs. Ellison for getting her head out of a certain orifice. Even if it took a near-death experience to force the issue.

I’m not the only one who thought for a minute there that Dead Mom wanted both New Mom and Martha to join her in the afterlife, right? But no, she just wanted to make a firm disciplinary point. We can all be glad that she shares powers but not moral tendencies with a certain wendigo.

The near-accident is, in fact, the only really frightening thing in the story. The matron is frightened by plenty of other things, but chiefly seems to find the mere idea of the supernatural Not Okay. She’s at equal pains to warn Mrs. Ellison that she’s dealing with a ghost who buys children circus tickets, and to claim that she doesn’t believe in any such thing. On the one hand, the inexplicable intrudes itself into ordinary life, eek. On the other hand, think of the number of maternal ghosts who’d have pushed another kid down the stairs so Martha could take their place, or released a lion to take bloody vengeance on the “luckier” kids.

Such a ghost might well stand between Martha and a new mortal parent “like an invisible wall,” or leave marks “that time could not erase.” But really, in this case, negotiation seems very possible. Especially if successful compromise comes with circus tickets and never having to wait for a doctor’s appointment.

Closer… closer… next week, join us for Chapters 49-51 of Pet Sematary.