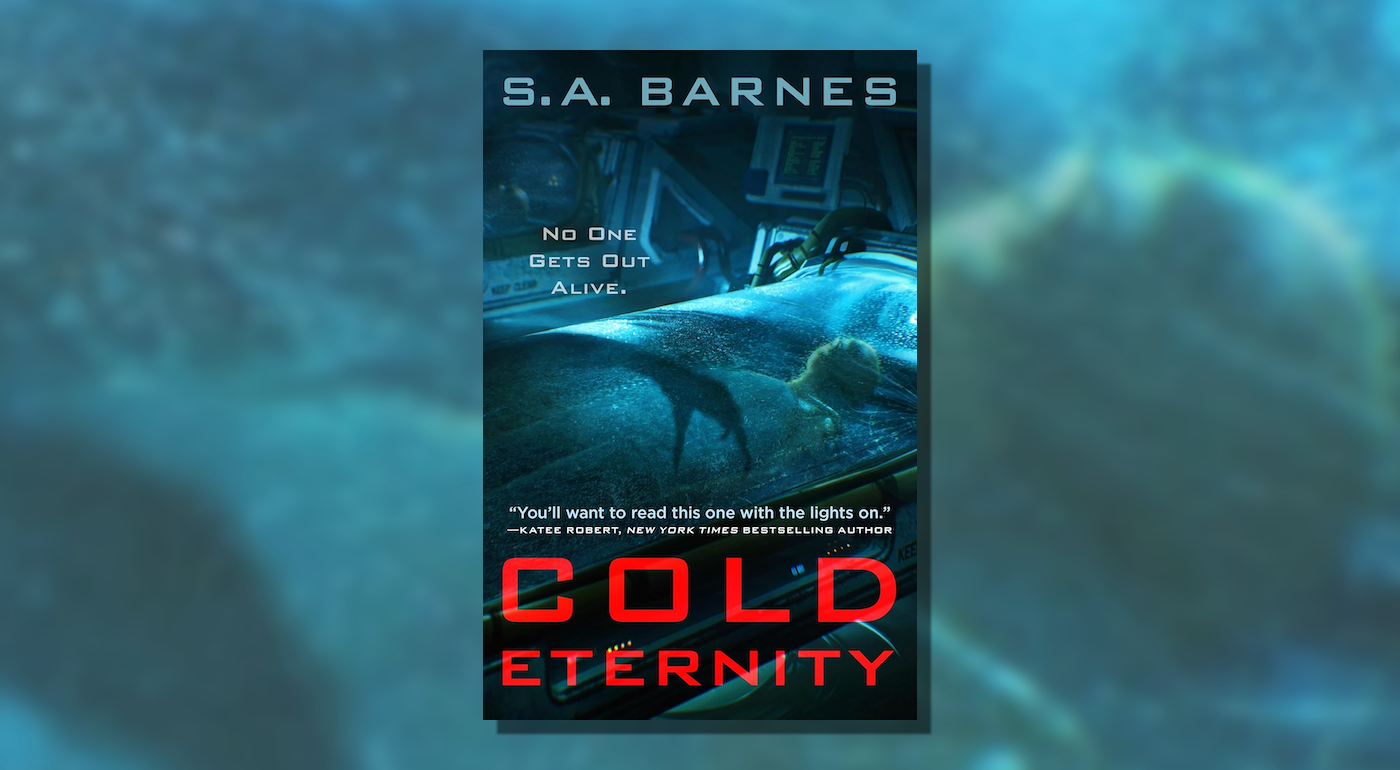

We’re thrilled to share an excerpt from Cold Eternity, the newest action-packed space horror novel by S.A. Barnes, out from Nightfire on April 8th.

Halley is on the run from an interplanetary political scandal that has put a huge target on her back. She heads for what seems like the perfect place to lay low: a gigantic space barge storing the cryogenically frozen bodies of Earth’s most fortunate citizens from more than a century ago…

The cryo program, created by trillionaire tech genius Zale Winfeld, is long defunct, and the AI hologram “hosts,” ghoulishly created in the likeness of Winfeld’s three adult children, are glitchy. The ship feels like a crypt, and the isolation gets to Halley almost immediately. She starts to see figures crawling in the hallways, and there’s a constant scraping, slithering, and rattling echoing in the vents.

It’s not long before Halley realizes she may have gotten herself trapped in an even more dangerous situation than the one she was running from…

1

EnExx17 Station, SL-23

United Nation of Colonies

Enceladus, 2223

Seven Fathoms, the establishment in question, is on station level twenty-three.

I’ve never been down that far, and when the lift doors open to reveal my destination, I hesitate. Theoretically, the narrow oval concourse on this level holds a variety of commercial and trade operations—places for residents on nearby levels to eat, drink, buy new boots, or trade for whatever you might need that someone else is willing to give up.

But a lot of the businesses appear shut down, closed up with heavy security gates… which have been trashed and bent inward anyway. People are gathered loosely in groups, talking loudly between fits of coughing, or sit crouched near the floor, their heads bent toward one another and their hands outstretched toward the warm air pumping out through the vents.

It’s darker here, too, lights pulsing erratically overhead in twitchy blue-white strobes, on the edge of breakdown. The air is worse, thicker somehow, like I can feel particulates lodging themselves in my lungs.

In my five weeks here, I’ve never ventured more than a few station levels from my very shitty hostel room on SL-9. Theoretically EnExx17 station security is present, keeping the peace everywhere. But they don’t seem to be here right now, not that I can see, anyway.

Today, though, I don’t have any choice.

The lift gives a warning ping, about to close its doors, but I’ve spotted the pub on the far side of the concourse, almost directly opposite me. Seven Fathoms is one of the few doorways still lit and seemingly operational. Raucous laughter spills out toward me.

Ignoring the nerves coiling and twisting in my gut, I step out of the lift and tug at the ragged edges of my sweater hood to shadow my features as much as possible. In doing so, though, my fingers collide with the swollen and tender flesh around my left eye. Sizzling lines of pain explode outward.

I grit my teeth, but after a moment, the sharpness fades, the injury resuming its regular dull ache.

All the more reason to get on with it, Halley.

I stride toward the pub, trying to find the fine line between moving with confident purpose and, well, running. The second I move, I can feel eyes on me, attention stripping away my illusion of invisibility.

I don’t belong down here, and they know it.

These people need help. Better conditions, a small voice in my head insists. If you—

No longer your problem, no longer within your power to play hero, remember? A louder, mocking voice cuts off the other.

Right as I near the pub, a man stumbles out, almost colliding with me at the entrance. His eyes are glazed, his coveralls still covered in white dust from his shift at the desalination plant. A briner.

Swaying in place, he stares at me, and I flinch and duck my head automatically, but there’s no shout of recognition, no slurred proposition.

After a moment, he stumbles off to the right, staring up at something no one else can see.

I grimace. That’s not alcohol. Daze, if I had to guess. At levels that might have him forgetting he needs to breathe, if he doesn’t topple over a safety railing or down a set of stairs first.

Nothing you can do about it, keep going.

Buy the Book

Cold Eternity

I duck into the pub, tension building in my shoulders. My contact better be here. I need them to be here.

It’s even dimmer inside the pub—for atmosphere, for privacy, maybe. More likely to save credits on power. It takes a moment for my eyes to adjust. The dingy floor has given up any ghost of its one-time shiny metal surface. A thin coating of salt crunches beneath my feet with every step. Practicality for absorbing spills? Or a side effect of so much brine, all the time? I don’t know.

On the other side of the darkened room, closer to the bar, a half dozen or so surface workers gather around a larger table, their ruddy faces bent over their ale mugs.

In one of the privacy booths ahead of me, the curtains are only partially drawn, so I have a view of a slick-looking woman, dressed better than anyone in a six-level range and her hair pulled so tight into an elaborate braid that it barely moves as she argues with someone on the holocomm in front of her. A man, another briner in silt-covered coveralls, lies stiffly in the booth next to her, eyes wide and fixed on the ceiling.

Daze. I knew it. Dealer and another buyer.

People will always find a way to step on others, to create a seedy underbelly to any location, even on a remote space station, where it’s better to keep your head down and your eyes to yourself.

Before the dealer notices me, I make myself look away. I don’t need any more trouble.

I turn cautiously in a circle, checking the pub’s other occupants. Very few of them sit alone at a table, and those who are alone don’t appear to be waiting for someone.

My heart plummets. The posting—on a hidden branch of the EnExx17 internal net—had seemed to be too good to be true.

Caretaker/security monitor wanted for dry-docked ship. No experience necessary. Low wages, but room and board included. Must be comfortable with isolated working environment and limited outside contact.

Room and board without prying eyes or hands around sounded perfect. Maybe too perfect. But my weary brain sought—and found—rationalization. It was probably some wealthy owner, one with more vessels than good sense, who didn’t want his baby sitting empty for months at a time out here, no one but the quartermaster half paying attention to it. I wasn’t thrilled about the low wages part—I couldn’t live like this forever, and credits were the only thing that would eventually get me out, even if it was just to return home.

In my former life, the idea of responding to a post on a black-market employment board—one I’d only learned of by overhearing the other hostel residents discussing it—would have sounded as bizarre as shimmying naked on the floor of New Parliament. And equally as likely.

But that was the old me. The new me needs to eat. And find a safe place to sleep.

I draw in a breath, ignoring a protest from my ribs, to calm myself.

I’m probably too early, that’s all. I wanted to arrive before my contact. To be sure. Of what, exactly, I don’t know, as I have zero identifying information on who I’m meeting, other than the initial K.

I head for the nearest empty table with a view of the door. “Oi,” the bartender calls as soon as I pull out a chair. “No drink, no table.” She points to something behind me. Her arm is tattooed with rivets and metal joints drawn on the skin with startlingly realistic detail, and I try not gawk at the artistry of it.

I turn to see what she’s indicating.

No drink, no table. The words are scrawled on the wall in flickering and partly burned-out digital letters. Everything out here on EnExx17 runs on a shoestring.

Touching my hood to make sure it’s still in place, I head to the bar, keeping distance from the patrons who are hunched over it on their stools.

“Tea, please.”

The bartender arches an eyebrow but says nothing.

A moment later she has one of my last loose credits, and I have a thick and lumpily printed mug with a “station-conserved” tea sachet—gray and slightly fraying around the edges where it’s been less than delicately restitched after new tea leaves were inserted—bobbing around in my beverage like an elderly dumpling.

Once, I would have pushed the mug away, disgusted.

Today, I hold it tight, circling my hands around its heat, and inhale deeply as if the scent alone will help fill the growling hole in my belly.

I return to sit at my table, keeping an eye on the entrance. Willing K, whoever he or she is, to come.

I’m so busy watching the door, I nearly miss the bartender approaching my table. Her shiny metal prosthetic legs flash with the movement even in the dim light, catching my eye as she smoothly clicks toward my table. The tattoos on her arms match her legs.

I look up and automatically put my hand over the top of my cup—I can’t afford a refill.

Her gaze moves over my face, her mouth tightening at the sight of bruises. “You the one expecting a call?” she asks.

“Oh.” I sit up straighter, removing my hand from my cup. “No, I’m supposed to meet—”

“Then this is for you.” Her mouth pursed in distaste, the bartender holds up a holocomm, the round disc pulsing with a green light, indicating a waiting party.

Before I can respond, she slaps the holocomm down on the center of my table and clicks away, back behind the bar.

I stare at it for a moment, attempting to work out what’s happening. If this call is for me, maybe K is canceling?

No. No, no, no! Desperation makes an ugly crease in the calm I’ve been clinging to. I need this meeting to work out.

I reach out and tap the center button. The green light goes solid, and a wavy projected silhouette appears above the holocomm, a head and shoulders, facing away from me. The connection is terrible, loose and staticky, so it’s hard to see much more than that. Machinery rumbles in the background on the other end. “Hello?” I say.

The figure turns to face me, the holocomm image blurring with the movement and then reconstituting itself. It’s a man, his rumpled dark hair shot through with strands of silver, and eyes so pale they nearly seem see-through. The dark circles under his eyes, however, are plainly visible, as is the scraggly scruff on his chin from several days—or weeks—of not shaving. He’s at least a decade older than I am, late thirties or even early forties. “Finally!” he shouts over the background noise on his end. “You’re the one who responded to my posting?”

I sense heads turning in my direction. Wincing, I tug the holocomm closer and fumble to turn down the sound on the side. I would have taken a privacy booth if I’d known he was going to call in. “Yes,” I say, my voice hushed. “But I thought we said we were going to meet—”

“Listen, I can’t get away right now, so this is the next best thing.” He rakes a hand through his already messy hair. “I need someone right away. I’m in the middle of a massive system overhaul, and I can’t be bothered with this shit. I’m trying to meet their deadline, but I can’t be in two places at once. And the fucking board rules are ridiculous—”

“What shit, exactly?” I interrupt.

He pauses, looking surprised. “What I said in the posting. You walk around, keep an eye on things. Document any new repairs required. Alert me if anyone arrives. Punch a button for the micromanaging board of directors so they know someone’s awake and paying attention. That’s it. A ’bot could do it if they weren’t so paranoid.” With a scoffing noise, he shakes his head. “I’ve never seen such fucking neoluds.”

The latter clearly sounds like the greater sin of the two, in his mind.

“I need someone reliable,” he says, turning to look at something behind him, off camera. Metal clanks against metal, and he swears softly. “Someone who’s not going to panic and fuck off in the middle of rounds like the last one.” His voice is muffled, but the disdain comes through loud and clear. “Stowed away on a transport during a resupply.”

Panic? Why would someone panic?

I open my mouth to ask that question, but he keeps talking, facing forward again. “What’s your name again… uh, I have it here somewhere.” He scowls at the something below the sight line of the holocomm camera.

I clear my throat. “Halley. Halley Zwick.”

“That’s it!” He grins. “As in Fireman Flick and Spaceman Zwick?”

This is the problem with relying on low-end criminal help; you get low-end results. Like someone thinking it’s funny to give you a false last name—to go with your equally false first name—based on a famous children’s cartoon character. Perhaps I should be grateful that I’m not Halley Mouse or Halley McDonald, though the latter, at least, could be a real name.

“The very same,” I say tightly.

His smile fades a bit, an avaricious look of curiosity sliding to the forefront.

“I noticed you didn’t include UNOC creds,” he says, his tone light. “Halley, was it?”

I stiffen, resisting the urge to retreat into the shadows behind me. I can’t tell if he recognizes me. Even with the damage to my face and the steps I’ve taken to alter my appearance—chopping off my hair, buying a cheap color enhancer to turn it an awkward auburn, and contact lenses without the comm hookup for their pale violet shade alone—it’s not impossible. Especially after that fucking press conference the other day. My mother in a soft and shapeless pale blue sweater that I’d never seen before— that she would have died before wearing—her hair loose around her shoulders, my father with his shirt rumpled and tie loose at his neck. “Come home, Katerina, please.”

They were the very image of worried parents. If you didn’t know them. But I do.

I make myself stay still, my face the practiced impassive mask I’d learned long before coming here. “Yes, it’s Halley,” I confirm. And nothing else. “K” was welcome to interpret silence however he liked—as if someone going by a single initial has room to criticize—but I wasn’t going to help by filling in the gaps.

“Uh-huh. Looks like someone did a number on you, eh?” He eyes me speculatively, waving his hand around to indicate his own face, and I brace myself for more questions.

But then he seems to come to a decision, shaking his head. “Listen, it’s an easy gig. You do your rounds, you pay attention, you press a button for the board of directors. You don’t mess with the residents or their shit, but keep an ear out for any of the pre-alerts, because the system is slow sometimes and every minute counts when you’re talking about—”

“Wait, wait. Residents?” I lean forward, heart sinking. “Your posting said the ship was empty.” Actually, it said dry-docked, and I assumed that meant empty, but still.

He grimaces. “It is. Technically.”

Technically? Not good enough. “Mr. K, or whatever your name is,” I begin.

“Karl,” he interjects.

“Fine. Karl. The ship either has passengers or it doesn’t,” I say.

“It’s both. Sort of,” he hedges.

“Okay,” I make myself say, reaching for the holocomm. “I think this is where we should part ways—”

“‘Residents’ is the term the board prefers,” he says quickly. “But it’s not what you’re thinking—not who.”

“Board? You keep talking about the board.” Corporate-owned ships might have a board of directors somewhere in the mix, but never this hands-on. There would be whole departments, maybe even divisions, responsible for their fleet.

Hesitation visibly shows on his face. “It’s the Elysian Fields,” he admits after a moment, with chagrin.

I rock back in my chair in surprise, before I can hide it. “You’re kidding. That’s still around?”

Irritation flashes across his face. “Why does everyone say that? It’s not going anywhere.”

I raise my eyebrows.

He makes an exasperated sound. “Except on its preprogrammed course, yes, yes, okay.”

So, not dry-docked at all, then. But not a normal ship, either. I could see why he maybe hadn’t wanted to try to explain that in the limited space of an illicit job posting.

“But I remember reading that it closed, what, thirteen, fourteen years ago,” I say. My class trip there, when I was twelve, must have been one of the last groups through.

“We closed to tourists, yes, but the Winfeld Trust ensures we’re still up and running.” He glances over his shoulder with distaste. “Barely, at any rate.”

The Elysian Fields is a relic. Over 150 years old, probably, at this point. I don’t remember the exact date it started. It was back in the early days of system colonization. Colonies were established and growing rapidly on Mars and the moon, along with the ill-fated attempt on Venus. Not to mention the first batch of residential space stations. More people were living in space or off-Earth than ever before.

And dying there, too. From accidents, like Venusian II, but also from normal causes, too—old age and disease.

Which raised the never before considered issue of what to do with the deceased. For large-scale contamination events, like the Ferris Outpost tragedy, protocol was the same then as it is now: the deceased, habs, and equipment are destroyed, burned to ash. But for individuals back then, it was more complicated. Cremation polluted the hard-won breathable air. Burial within the colony domes took up incredibly valuable land that could be used for crops or building. Ejecting bodies from the stations created minefields of tiny human missiles in orbit around them, making it difficult—and extremely horrific at times— for ships to navigate… without collision.

In this narrative space, Zale Winfeld, the wealthy trillionaire and tech genius, became the hero. Winfeld had one of those late-in-life conversion experiences, only instead of finding God, he seemed to think God had found him. He’d received a vision, he said. God had chosen him to spread the word of the new world that was to be. He “donated” a former hospital ship, converting it to the latest in cryogenics. According to Winfeld, death was only temporary, until technology caught up and allowed everyone to live forever. Defeating death—that was to be his big legacy. Available for a price, of course.

In an irony of ironies, Winfeld himself didn’t get a chance to use his own innovation. He vanished not long after a shuttle crash took the lives of his three children (and his fourth wife). His company desperately tried to suggest he’d simply retired from public life, but persistent rumors were that he’d committed suicide, out of range of Elysian Fields, unwilling to be “saved” without his family at his side.

Eventually, the better part of a century later, the ship was turned into a public memorial and an educational experience (aka revenue generator).

A history lesson, a field trip for the kiddos, with a side of morbid gawking. Not all that unusual, I suppose, considering a few centuries ago people used to picnic in graveyards on Earth, and stare at the mummified dead inside glass cases at museums.

Still weird, though.

I remember looking through the frosted side of a cryotank at an aged pop star, someone who had been dead before my grandmother had even been born, her light brown cheeks still so perfectly preserved that I could see traces of makeup and the delicate fuzz on her hardened, frozen skin. Glass display cases around her “room” housed sequined tour outfits, guitars, and replica wedding rings from her famous marriage to a vid actor that lasted less than a week. Holos of her much younger self gyrated around us, as the boys in my class unsuccessfully attempted to peer through the tank privacy shield protecting her naked corpse. Or near-corpse, if she was frozen in time.

And the “show,” featuring AI versions of Winfeld’s deceased adult children welcoming you to the ship and expounding upon the benefits of joining Elysian Fields, was especially eerie.

Even now it sends an uneasy prickle over my skin.

Most of the “dead ships,” Winfeld imitators, went out of business a long time ago, especially once biocremation became accepted as a practical solution. But apparently Elysian Fields is still out there.

“I can’t manage their stupid security requirements and finish this upgrade in time. But the board won’t hire anyone to help me, so I’d be bringing you on… unofficially,” Karl says.

Illegally, is what Karl means. Elysian Fields is an Earth ship, of the former United States, so Earth law applies. That means UNOC credentials are required, and Earth citizenship is vastly preferred. Yet another way the legacy governments try to stem the tide of progress, by implementing stiff fines and even short stints in prison for employers who don’t follow the rules.

The Winfeld Trust would never take that chance, but Karl apparently will.

“I will, of course, have to tell them you submitted fraudulent credentials if we’re caught,” he continues easily.

There it is.

Creating fraudulent UNOC credentials is an automatic sentence to a decade of labor on one of the asteroid mining camps, which is why I hadn’t gone that route. So far, nothing I’d done had broken the rules, just… bent them at a severe angle. I still want my life back. Someday.

“Of course,” I say dryly.

“But I’m sure we would both prefer that not be the case,” he finishes.

It would be his word against mine, if that were ever an issue. He might find himself surprised at who was willing to fight for me, if only to have me back within their control. Still, Karl wouldn’t want that trouble, and neither do I.

And the primary benefit of this arrangement remains: I would be hidden away where no one, including my former employer’s vast network of contacts, would expect to find me—or even consider looking, really. I wouldn’t have to try to sleep with my back against the door, knowing that even that measure wouldn’t be enough. Instinctively, I trace the lower edge of the swollen skin around my eye.

Metal screeches loudly in the background on Karl’s end of the connection.

“I have to go. If you think you can manage it without letting this place get into your head like the last guy, you’ve got the job. Seven hundred fifty credits. I’m expecting a water resupply shipment from EnExx17 in, uh, twelve hours. If you want—”

“Seven hundred fifty credits an hour? That’s barely minimum wage by UNOC standards.”

He makes an exasperated noise. “Seven hundred fifty credits a day.”

I gape at him. At 750 credits a day, it’ll take six, almost seven months to save up enough for transport back to anywhere civilized. Way longer that I anticipated being on the dark side of nowhere. And that’s if I don’t spend any.

“Housing and food are included in this gig,” Karl reminds me. “As for UNOC standards, you can go ahead and report me.” He grins.

“Twelve hundred,” I say quickly.

Another loud crash echoes on Karl’s end.

“One thousand credits. Final offer. If you want it, be on the transport ship in twelve hours. Terminal B, Gate Thirty-Four.”

His image vanishes, the connection cut, before I even have a chance to respond.

I sit back in my chair, staring at the space where his holographic image was. His offer is insulting, not to mention illegal, but if I say no, he’ll have plenty of other takers. By the time I sent my information in, the number of responses, ticking upward in the corner of the posting, was already in the hundreds.

I’d been surprised when I got a pingback to meet for an interview at the Seven Fathoms. Surprised and relieved. If “relief” can adequately convey the warmth of muscles relaxing for the first time in months and dizzying rush of a true, deep breath.

It was one of those moments when you don’t realize how worried you actually were until you can finally see your way out from under whatever it is that’s sitting on your chest like a six-hundred-ton baroque cruiser.

But… an isolated ship of the dead, by myself, except for one guy who has already admitted to the potential criminality of his character by posting this job to begin with.

I shudder. It’s not ideal.

But creepy as it is, the Elysian Fields is at least somewhat familiar. And the job sounds easy enough.

Plus, I’m not sure I have an alternative.

Two nights ago, I woke to hands yanking roughly at me, rolling me off my thin mattress. A bash to the side of my face stunned me, and when I hit the ground, a fist in my hair at the back of my head held me down. A harsh voice, telling me, “Stay quiet if you know what’s good for you.”

Numbness washed over me, even as a little voice in my head kept protesting that this couldn’t be happening, even though I’d been half expecting it. But I was so careful!

The fear, so sharp and bright, a knife’s edge glinting in the darkness, felt unreal. Not the hazy featureless terror of a nightmare, but the pure disbelief. Life colliding at speed with my false sense of security.

When the numbness finally wore off, only a few seconds later, I lashed out, flailing, kicking and bucking. I would not be taken quietly. And if they were going to kill me, I would not make it easy for them.

That “fight” earned me a likely orbital socket fracture— the auto-doc holo could only give it a 75 percent accurate diagnosis without more personal information that I refused to give—a concussion, and several cracked ribs.

But they didn’t drag me out of the room, didn’t slip a blade between the ribs that now pained me.

They took my hard credits, though. Without my UNOC credentials, I have to rely on a physical credit chip to hold most of my money. Once they found that—poorly hidden in the toe of my boot, I realize now—they left.

A robbery, plain and simple and ugly. Reassuring in its mundaneness if nothing else.

Or that’s what they wanted it to look like.

I try to ignore the little voice in the back of my head.

It’s not as if my credit chip was a big secret—the pinkish scar on the back of my hand where my UNOC implant used to be is a dead giveaway that I have to use some other means of payment. It makes me an obvious target for random criminals who are paying attention.

The problem is, I can’t be sure.

You saw the mark on his wrist. How many people have that exact tattoo?

Except I don’t know what I saw. It might have been the angled line of a shield, the tail end of a familiar Latin phrase, peeking out from under a sleeve as one of the intruders held me down. Or not.

The brain is notoriously unreliable in stressful situations, and it was only a glimpse. I might have… filled in the gaps with my worst-case scenario, letting my worries get the best of me.

With something that looks like “Mors mihi lucrum”? Really?

The memory—the cold metal floor pressed into my face, the acrid scent of sweat above me from the man whose rough hand tangled in my hair—fills me with a bright bolt of pure, crystalline fear.

If it was them…

I shake my head, refusing to follow the thought any further. It doesn’t matter. What does matter is that I’m not as invisible as I thought I was. And if random criminals can find me so easily, what about the professionals who might be looking?

I can’t take that chance.

I stand up and grab the holocomm. Life is full of hard choices, but this isn’t one of them. I have nothing to fear from the dead, and one possibly shady man is nothing compared to a station full of them.

Pulling my sweater cloak tighter around me, I head toward the bar. The bartender is occupied with another customer, a man hunched over the bar, his face turned away from me. He’s dressed all in black, unusual out here, and his shirt and pants are pristine. Not even so much as a smear of salt on them.

Like, say, a UNOC Investigation and Enforcement agent’s uniform with all the shiny bits and bobs, ceremonial braids and division patches, removed to help him blend in.

Shit. I slide the holocomm onto the scraped and battered bar surface and turn to head for the door. Quickly.

“Hey,” the bartender calls after me.

I freeze, heart skittering in my chest like a small frightened animal. “Yeah?” I make myself say, without turning around. Never turn around.

“That guy? He’s ‘interviewed’ people from here before,” she says with distaste. “Never seen any of them come back.”

Because they panic and take off in the middle of the night, apparently, if what Karl says is true. Or at least the most recent one did.

I nod, acknowledging the warning. “Thanks,” I say, and then keep walking, expecting a shout of recognition from the possible IEA agent—or, worse, a hard hand gripping my shoulder. But I make it to the corridor without interference. For now.

In truth, if this Elysian Fields thing works out, or even if it doesn’t, I won’t be coming back here, either.

2

Terminal B, the transport deck, is a patchwork of chaotic sounds and colors. Failing lightbars overhead flicker a sickly yellow or pulse a dull gray-blue. Dozens of voices speak over one another, in as many languages, competing with transport captains shouting for any last-minute passengers. Food vendors demand attention for their hot and (theoretically) fresh wares. All this is punctuated by monotone departure and arrival announcements on the overhead, creating a din that feels as if it should be solid to the touch in the air around me.

I keep my head down, watching as discreetly as I can for UNOC IEA agents. I haven’t seen that one from the bar again. But now that I’m here, so close to escaping, it feels inevitable that dozens of them are lurking in the shadows, waiting to surround me.

I press the loose edge of my sweater cloak against my nose as a barricade to the smell. It reeks up here, despite the higher level. Beneath the bacon-flavored soy dogs rotating on a spit, the sweet-salty scent of teriyaki noodles from the stand farther down, and the hot-oil aroma of paddle cakes behind me, a strong odor of rotten eggs and old fish lingers. My throat works in a precursor to gagging, and I press the woven fabric tighter, as if that will help filter clean air through to me. But there’s no escaping that smell, not here. That’s the brine.

Huge barrels of it are being carted this way and that to various transport ships, some for local stops, most to transfers to larger depots that will take the brine to farther-flung locations. Earth, even.

Water, too, rolls by, on thundering carts filled with equally large barrels, but transparent, the better to advertise the quality of the product. All of the barrels are branded with the EnExx17 designation, as are the well-armed station security guards accompanying each cartload.

Not that anyone out here cares. Clean water—or a lack of it—is not an issue on this station. It’s the reason most of the workers took the job. Comes with the wages, part of the benefits package. Though in that way, I suppose it costs dearly enough.

Exhausted-looking briners talk in small groups, awaiting transfer to a different EnExx station. Some of them have their families with them, children, too. Dressed well enough, in clothes from the exchange, but too quiet, too skinny. The ashen quality of their skin speaks to too much time on the lower levels without any access to the limited sunshine or even the sun lights in the simulated outdoor areas that are supposedly for everyone. Knobbly joints, visible through their thin layers, say they’re not getting enough of their nutrition from actual food, relying instead on VitaPlex. Supplies aren’t reaching them, or the higher-level executives aren’t sharing. And no one in the local gov is paying attention.

Or they’ve been paid to direct their attention elsewhere.

One of the children, a boy of about eight or so, points to the paddle cake vendor behind me. His father reaches down and takes his hand, lowering it, before shaking his head and speaking quietly to him.

I can’t hear the words, but I get the gist.

My eyes burn, and I have to look away, stuffing my hands into my pockets. In the bag strapped tightly to my side, I have only a few clothes and toiletry items—nothing of any value. If I had the credits, I would buy that kid his paddle cake. His sisters, too. Not that that would come close to assuaging my responsibility. But I don’t have it. Once I reclaimed my advance from the hostile hostel for the nights I wouldn’t be staying— the manager tried to keep it, claiming some kind of deposit until I pointed to my banged-up face and reminded her that I had no problem advertising what kind of establishment she ran, which, of course, I couldn’t actually do, but she didn’t know that—I had just enough for a ticket out of here.

In my pocket, I close my hand over the battered token, a physical chip of blue plastic with the transport’s designation crudely carved into its surface. Because I had no UNOC credentials to hold my ticket. Another reminder of my current status in life—a nonentity.

And that was the best choice I had, my only choice.

If you’d sucked it up and stayed, played along like a member of the team…

Guilt pulses through me, and I turn away from the little family, focusing on something, anything, as a distraction. A battered departure screen, jagged white lines running through the transport designations and times, hangs crookedly on the wall opposite.

It’s mostly impossible to read, but that doesn’t matter. It’s a safe place to fix my eyes for the moment.

Until it starts flashing images of people with the designation “missing.”

Grigory Eachairn

Julia Jordan

Caspian Ahmad

Shikoba Ludwig

Johannes Salvi

Trinity Boothe Hopkins

Astra Sandberg

Giannina Ngo

And with every picture, a repeated refrain: “Please report any sightings! Hard credit reward! We want our [child/daughter/ son/parent] to come home!”

Families desperately searching for their lost loved ones who’ve disappeared from EnExx17—they must be desperate if they’re relying on this method to reach people.

Some of them are probably runaways. A handful of the disappearances might even be human trafficking, given the volume of transports out of EnExx17. But based on my station experience, I’m betting a good percentage of them are folks who descended into the lower station levels in a Daze haze and never resurfaced. Eventually, they’ll be presumed dead, then found sometimes many months or years later, as a funky smell or bones in a passageway thought to be closed off.

I can’t seem to look away. As I watch the faces flicker overhead, part of my brain automatically conjures possible programs and initiatives that might be implemented to address this issue, from the introduction of an on-station rehab facility (UNOC-funded, of course) to tighter restrictions on cargo haulers that might be tempted to include humans among their wares.

Until, of course, my own face appears. Right there, on the board above me.

My lungs lock up, and I can’t move. The noise of the terminal drops away, leaving only a high-pitched buzz in my ears. Who… How did they…

It takes a moment for my stuttering brain to begin to process information again. But eventually, more details seep in. The name next to the face: Sarai. The last known location: here on EnExx17, somewhere on SL-19. Her brother’s contact information.

My breath rushes out of me in a quiet whoosh. It’s not me. I don’t even have a brother.

This girl, Sarai, bears just enough of a superficial resemblance to me in my old life—blond hair, blue eyes, though she’s several years younger—that my paranoid, sleep-deprived brain filled in the gaps.

Also, Halley, your face wouldn’t be on that board for panicked families.

It would be on the holocomms of every passing security guard and IEA agent on the whole fucking station.

Jesu, I need to get out of here.

[“Hey, gerla, are you getting on or what?”] A man’s voice behind me shouts in Russian, the sharpness of the demand cutting through the noise around me and inside my head.

I turn around. The first mate I bought my ticket from, a broad, balding man with an impressive beard, is gesturing at me with wide exasperated movements that translate in any language. The small cluster of waiting passengers, including that little family, is gone, presumably already boarded.

Without thinking, I call back, [“I’m coming. Don’t rush the horses.”]

His brows rise.

I ignore his expression of surprise and duck my head to hurry toward him, my worn boots clacking hard across the gritty floor and onto the loading bridge.

[“Okay, strange woman,”] he mutters.

The inside of the transport is like every other independent transport ship I’ve been on, which is to say, like the one I came here on—a former cargo hold retrofitted as a passenger area because ferrying people became a more profitable endeavor and lower licensing fees made it possible. About thirty mismatched seats of varying colors and ages are intermittently and randomly bolted to the metal floor in haphazard “rows.” Several unevenly placed windows carved into the sidewalls offer a little additional light, along with something that might be generously considered a view. Everyone else is already settling in, talking in low murmurs as they rustle and shift their bags into place, restraints clicking.

I head for the only open seat, crammed against that sidewall— the first to be sucked out in the event of a hull breach. Probably not quite legal. A man, a midlevel EnExx manager, based on his too-clean beige jumpsuit and the designation on his shoulder, is already in the seat next to it, blocking my path, his eyes closed and his hands folded in his lap.

I know this trick. He wants this “row” to himself. It doesn’t work, though, when there’s only one available seat left.

“Excuse me,” I say, keeping my voice low but firm. “I need to get through.”

He doesn’t so much as twitch.

“Sir?” I try again.

Again, nothing.

My temper flicks to life. I want out of here. And this guy is determined to make things difficult. His workers probably hate him. A self-important asshole who thinks that because he runs some tiny square inch of the world, he’s better than everyone else. Particularly an annoying woman in worn-out clothes from the station exchange who thinks she has the right to take space he’s already mentally claimed as his.

Fine.

“Sir, I don’t think you should be touching yourself like that here!” Not too loud, don’t want to cause an actual stir. Just make him think I might.

Midlevel Asshole bolts upright, eyes bulging open, hands flying away from his lap, like his thighs are electrified. “I’m not!” he blusters immediately.

I smile politely. “My mistake.”

He glares at me and then wrestles to free himself from his restraint with a huff.

It used to work better, when I was in a crisp suit, official insignia on my lapel, and UNOC credentials prominently displayed on the back of my hand instead of the still healing scar from their removal—a signal to some that they have permission to offer abuse and mistreatment without fear of consequences.

But it still worked.

With grim satisfaction, I back up to give him room to stand and step out of the way. That’s when, through one of those odd hushes that sometimes falls over a crowd, I hear a woman’s voice behind me, clear, smooth, and professional.

“… entering week six of the hearing. The prime minister of the United Nation of Colonies has continually denied the allegations, calling them ‘ludicrous’ and ‘a conspiracy’ to muddy his good name.”

I freeze, my brain shouting contradictory orders at me: Duck down! Pretend everything is fine!

I manage to twist around to see where the woman’s voice is coming from.

An old vid screen is welded—and then apparently duct-taped for good measure, the silver tape framing the edges—to the bulkhead wall at the front end of the “passenger compartment.” One of the perks of choosing this transport, apparently. At the moment, it’s playing a fragmented, jumpy picture of SNN and one of their political reporters, Lanna Charles. No holo, but this is bad enough.

My heart immediately trips with anxiety.

Are they going to show a clip, archival footage with my face in the background? Worse, what if they run that press conference again?

“Are you sitting down or what?” Midlevel Asshole demands, at a far higher volume than I used.

I swivel automatically to face him, his flushed cheeks. Other passengers are staring. At him. At me.

Sit down. Halley Zwick has no reason to care about this story. Go! The exasperated voice in my head, so familiar, immediately spurs me into action.

I turn my back on the screen, pretending it doesn’t exist, and squeeze past manager man. I unclip my bag and force myself to settle into my seat. Next to me, the midlevel manager drops back into his seat with a loud, disgruntled exhale, before pulling a holocomm from his pocket and flicking through his messages. By fate or poor luck, though, I have a clear view of the vid screen between the headrests of the seats in front of me. And I can’t make myself look away.

“… representative from the Ministry of Justice has indicated that the possibility of criminal charges for Bierhals’s alleged role in inciting a riot has not been ruled out at this time,” Lanna continues. “He is alleged to have planted operatives of his own in the crowd, as false supporters of his rival to encourage the lawlessness that resulted in twenty-seven injured and three dead. One thing we know for certain is that the violence on Nova Lennox likely changed the outcome of the most recent election. With that violation of terms, UNOC removed the station’s capacity to vote as a probationary member of the body. But anonymous sources have indicated that Nova Lennox would have cost Prime Minister Bierhals his election, giving the win to Rober Ayis.”

On screen, Ayis appears, red-faced and gesticulating wildly. I can’t hear his speech, but I don’t need to. It will be about the evils of UNOC and Earth’s legacy governments and how each station needs to put itself first. One Station is his program for self-sufficiency.

Then, it cuts to Prime Minister Mather Bierhals, young, handsome, flashing a modest grin—Not so many teeth, goddammit, Math!—and holding a hand up to a crowd in a benevolent wave. He stops briefly to shake hands, bending down to speak to the children directly, Mather’s go-to move for winning attention from the press and the public. Kids greet him with bundles of wheat grown in the dome fields, and teens hold up holos of their art projects, sponsored by Mather’s new Art Is Universal program.

The contrast is striking. And beneath layers of despondency and exhaustion, pride swells in me. Just a little.

The camera catches Mather chatting with one girl in particular, his face intent on her words, nodding as she speaks. That is his gift, making people feel heard. Behind him, his team follows, discreetly taking notes on everyone he speaks with, making sure to mark a need for additional communication or perhaps even a personal note.

An odd distant ache starts up in my chest. Watching him, watching them, is like seeing someone you used to know, an ex-boyfriend, a friend you no longer have contact with, from across a busy shuttle station. You are no longer part of their life.

I tear my gaze away from him to study the background of the video. This looks like a clip from a visit to the Columbia Hills colony, based on faux Greek architectural elements in the printed housing behind him. It was a big deal at the time, moving away from the practical but sterile hab style that has dominated dome living for so many years. One of Bierhals’s innovations, back when he was in Parliament, to make a house feel more like a home. Studies showed improved mental and physical health as a result.

Theoretically. I don’t know. I don’t know anything anymore. “Much of this will depend on the results of the New Parliament’s ongoing committee investigation into the allegations, including finding witnesses to testify,” Lanna says, “which has been difficult, given the high turnover in the new Bierhals administration. Some have even suggested that it’s a conspiracy to keep former staffers from speaking out.”

Feeling the heat of an invisible spotlight that only I’m aware of, I sink down farther in my seat, now grateful to have the innermost, instant-death position. It feels more protected, less visible.

“There’s really no story here, Lanna. Turnover early in a new administration is completely normal.” This new voice from the news freezes me in place. It sounds like the one in my head.

Niina.

Except the real Niina sounds more wryly amused than the version in my head. And her true voice has the tiniest tinge of irritation that makes you want to rush to soothe, appease. To win her approval.

Or maybe that’s just me.

In the gap between the seats, I catch a glimpse of Niina on the screen. As always, her confidence projects outward, from the precise cut of her black hair—perfectly even at her chin—to the ruthless arch of her eyebrows. She looks as if she’s never been stressed or worried about anything in her life. She’s someone who knows her value, who knows the power she holds and doesn’t bother to hide it.

She is who I wanted to be, once. And she made me believe it was possible. Another, stronger pang of longing clutches hard at my heart, before I ruthlessly push it down.

Niina had her own reasons for doing what she did and none of them had to do with me.

Though I can’t see him on screen, Harrison Butler, my replacement, is surely lingering nearby. Ready to jump in with facts, contact information, or Niina’s current nicotine fixation. He’s a high-cheekboned, camera-ready Harvard grad who favors tidy eight-button suits and doing what he’s told. That will serve him well.

“We’re transitioning from campaigning to active governing, and some people aren’t cut out for that. So we’ve had to make some adjustments.” Niina’s gaze seems to bore straight into me.

My face flushes hot with a confusing blend of humiliation and fury, and I have to look away, studying the lumpy seam of metal around the window until I can wrangle myself back under control.

“That was Bierhals’s chief of staff, Niina Vincenzik,” Lanna says. “She indicated that every member of the campaign staff has been encouraged to testify as called upon. With the appropriate subpoenas. But as some have pointed out, it’s hard to subpoena people you can’t find.”

I brace myself for a clip from the press conference. My parents “pleading” with me to return.

But the anchor moves on to another story, thankfully, this one about a grain disease destroying huge swathes of crops in the New Boston dome, triggering worries about a lunar famine.

A to-do list forms in my mind before I can stop it: contact the New Boston governor to ascertain food stores, hound our media contacts into drawing more attention to the impending crisis because people can’t care about what they don’t know about, and pound on doors (metaphorically speaking) until I can get someone in the UNOC liaisons office to pester those cheap bastards back on Earth in the RusAmerSino Alliance for aid. The residents in New Boston pay taxes like everyone else and they—

No.

Not your job anymore. Not your place.

The despondency I’ve been battling for the last six weeks rises up and drags me under.

It doesn’t matter. None of it matters. It’s all bullshit. Fake power politics and manipulation. The world is a game, one in which you can’t win unless you cheat.

And, for better or worse, I’m out of the game.

I turn sideways, away from the screen and toward the sidewall all the better to be sucked out into space, if the opportunity arises—and drape the ragged side of my sweater cloak over my face to pretend to sleep.

Surprisingly, exhaustion is a relatively effective cure for my brand of fear-based insomnia. Or maybe it’s being on the move again, the engines thrumming beneath my feet in a reassuring hum that speaks to escape. Again.

I hadn’t realized how much tension I was holding, in my gut, in my shoulders, until the knots in both relax as soon as the transport clears the EnExx17 dock. No unexpected ATC holds or delays, no interruptions from an official IEA vessel demanding to board and search.

They always tell you when you’re lost to stop moving so searchers can find you. I’m hoping the opposite holds true as well.

I wake abruptly, with a stiff neck, sore knees from the tight space, and the vague knowledge that I’ve just missed some kind of announcement overhead. The vid screen is, thank God, dark now.

A quick look around the compartment shows that I’ve managed to sleep through several stops, including that of the manager next to me. His seat is empty, restraints dropped to the floor, as if they’re somebody else’s problem.

Asshole. I lean over and pick the ends up, piling the straps in the seat for the next passenger.

Gasps from the other side of the compartment draw my attention. A handful of people are whispering and leaning toward a window.

Oh, fuck.

My hands go numb. Are we getting stopped? Now? Out here?

But when I make myself stand, to the stares of the remaining passengers near me, and angle my body to peer outside the window, all I see is the sheer cliff wall of metal, growing closer as the transport edges into alignment.

We’re pulling up to a ship. A big one. The cargo hold doors are exposed, the connecting bridge already juddering forward toward us.

“See, right there,” a briner whispers to his colleagues, as he points upward out the window. “I told you.”

I give up any appearance of discretion and move closer to the window for a better look, excusing myself past the remaining passengers.

The briner looks up at me when I arrive next to his seat, but he doesn’t seem surprised. He points again.

Elysian Fields is painted along the side of the ship, in enormous sweeping letters, each one probably larger than this entire transport.

Oh. The ship is bigger than I remembered. But then again, I’d arrived last time on public education transport, holding several hundred students. And we had been welcomed into a public entrance rather than the (enormous) cargo hold.

The transport glides to meet the extending bridge, but the connection is more of a controlled crash, with a big jolt rattling the vessel around us, forcing me to grab an empty seat to stay on my feet.

“A supply drop for Elysian Fields,” the briner says a little louder, in response to the questioning looks around him. “The dead ship?”

My acknowledgment of curiosity seems to act as permission for everyone else to sate theirs; restraints click open left and right as passengers move closer to the window for a better look.

Grateful for the distraction, I slip through them, retrieve my bag, and head toward the rear of the passenger compartment for the cargo hold door.

A blast of brisk air greets me as soon as the door retracts. It’s much colder in here and reeks of ship mechanicals. Hot metal, dried-up grease, and unwashed bodies working round the clock. I suspect the crew may sleep in here, when they have the opportunity to sleep at all.

I wend my way through the stacked crates and barrels of cargo, toward the open door and bridgeway to the larger ship.

The first mate from before is directing crew members as they drag rumbling, squeaky-wheeled carts full of supplies from the transport across the bridge.

The Elysian Fields’s extendable bridge feels solid enough beneath my feet as I take my first step onto its patterned metal floor; I’ve heard enough horror stories about older ships to be cautious. The seal behind me isn’t hissing with a leak, and the much heavier carts don’t seem to be making the bridge itself wobble.

I reach the threshold on the other side without any incident. The Elysian Fields cargo hold is several levels tall and echoingly wide. I expect a clinical, antiseptic smell inside, but it’s mostly… old. That scent of decaying paper, glue, and materials that seems to inhabit any building over a hundred years old. Apparently that applies to ships as well.

On one wall, the towering metal launch framework for emergency escape shuttles stands empty. The shuttles themselves were probably removed when the museum was shut down. Less to maintain.

On the other three sides, mostly bare shelves line the walls to a dizzying height. A reminder that before this was a tourist stop, it used to be an active hospital ship, serving multiple colonies and thousands of people. One section holds boxes upon boxes marked Drexell’s Snack Mixtravaganza, stacked well above my head. Left over maybe from the food court days? I’m not sure.

Other crates on the lower levels of shelving are marked with scrawled names and numbers, making me wonder if they belong to the “residents.” A dozen or so empty cryotanks are shoved into the far corner, their attached tubes and wires stretching out in every direction, crawling across the floor like they’re reaching out for connection.

I shiver in spite of myself. Extra tanks, left from when the ship was still taking new residents probably. Or maybe spare ones in case of a malfunction. But they look so dusty and discarded, it’s hard to imagine them being of any use.

The supplies brought by my transport—dozens of crates marked with chemical compounds that I don’t recognize, plastic tubing on a roll that’s taller than I am, a few barrels of water, and a few small boxes of food—sit in the center of the cargo hold, an island in an ocean of empty space.

A blast of static makes me jump, and then Karl appears on the vid screen across the room.

“Thank you, gentlemen,” he says, his voice tinny and thin from the speakers. “I’ll take it from here.” As the crew members depart with their now empty carts, Karl’s attention turns to me, pale eyes laser-focused. “Halley. Good. The service lift is forward and to your left. Take it up to the main exhibition level, and I’ll give you a tour.”

I feel small suddenly, alone, here in this space with nothing but my tiny bag full of dirty clothes. Following Karl’s directions with my gaze, I see a darkened corridor at the front of the cargo hold with what might be an elevator entrance on the left-hand side.

At the opening to the corridor, a large sign with a directional arrow points deeper within the ship: prep rooms.

Of course. It makes sense that they would have received people here on the brink of death, cleaned them up, emptied them out, whatever was required to preserve someone back in those days.

I imagine pale limbs stretched out on shiny metal tables, hands flailing, blood running red and thick over the edges into a floor drain.

Knock it off. Nobody’s been bleeding on this ship in better than a century.

I don’t consider myself superstitious or even easily frightened. But something about being here with the idea of staying, rather than a short visit with a definitive end and accompanied by other people, feels… creepier than I imagined. And that’s without considering what possibly waits upstairs, in the auditorium.

“[You sure about this?]” the first mate behind me asks, startling me into turning to face him.

He’s at the threshold to the bridge, his presence keeping the cargo hold doors open and the bridge extended. His brow is furrowed almost into his former hairline. His skeptical expression takes in the dusty, oversize space, and me along with it. It’s as if he’s reading my mind.

Irritation flares within me. Not at him, at myself. No. I am absolutely not sure. But I am certain that I can’t afford to be unnerved by imaginary dangers and childish fears when very real, adult ones await me elsewhere.

I wanted isolation, I wanted the freedom to stop hiding, a safe place to plan my next step. Well, now I’ve got it.

Plus, I have no money for a fare back. There are exchanges that could be made to guarantee passage, but I’ve already bartered away enough of my soul to get this far.

I nod. “[I’ll be fine. Thank you.]”

Then I make myself walk away before I can change my mind.

Excerpted from Cold Eternity, copyright © 2025 by S.A. Barnes.