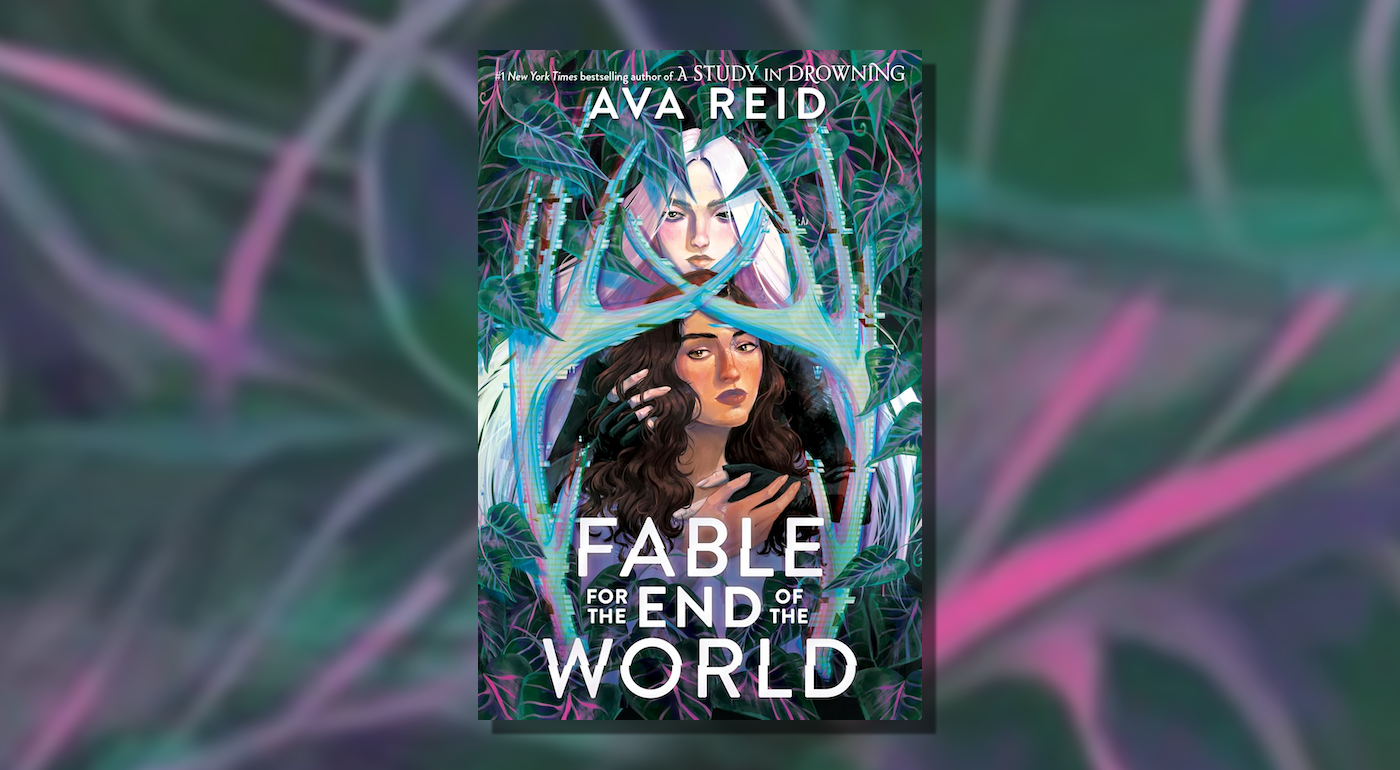

We’re thrilled to share an excerpt from Fable for the End of the World, a young adult dystopian SF novel by Ava Reid, out from HarperCollins on March 4th.

By encouraging massive accumulations of debt from its underclass, a single corporation, Caerus, controls all aspects of society.

Inesa lives with her brother in a half-sunken town where they scrape by running a taxidermy shop. Unbeknownst to Inesa, their cruel and indolent mother has accrued an enormous debt—enough to qualify one of her children for Caerus’s livestreamed assassination spectacle: the Lamb’s Gauntlet.

Melinoë is a Caerus assassin, trained to track and kill the sacrificial Lambs. The product of neural reconditioning and physiological alteration, she is a living weapon, known for her cold brutality and deadly beauty. She has never failed to assassinate one of her marks.

When Inesa learns that her mother has offered her as a sacrifice, at first she despairs—the Gauntlet is always a bloodbath for the impoverished debtors. But she’s had years of practice surviving in the apocalyptic wastes, and with the help of her hunter brother she might stand a chance of staying alive.

For Melinoë, this is a game she can’t afford to lose. Despite her reputation for mercilessness, she is haunted by painful flashbacks. After her last Gauntlet, where she broke down on livestream, she desperately needs redemption.

As Mel pursues Inesa across the wasteland, both girls begin to question everything: Inesa wonders if there’s more to life than survival, while Mel wonders if she’s capable of more than killing.

And both wonder if, against all odds, they might be falling in love.

Floris Dekker spreads his daughter’s body out on the counter.

“Please,” he says.

Sanne is still wearing a limp white dress, stained at the hem with what might be rust, but I know better. The drab linen, gray-hued and rough from too many washes, indicates a Caerus online catalogue purchase. The seams are straining around her shoulders and elbows. Something from the back pages, cheap and mass-produced.

“No,” I say firmly. “No way.”

“Please,” Floris says again. “This is all I have left.”

Strictly speaking, he’s wrong. Sure, his wife, Norah, has been dead since spring—from drinking contaminated water; if he lived in Lower Esopus with those of us who don’t have indoor plumbing, she’d have known to boil her water before she drank it—but Floris still has plenty of her left. All her Caerus debts, floating around the empty house like ghosts, wrapping their cold hands around his wrists and ankles, spectral manacles.

And now, even with Sanne dead, he’ll have company. She was twelve, old enough to accrue her own ghosts.

“I’m sorry,” I say.

Sanne’s hair is damp and tangled. If I didn’t know better, I would say she died from drowning. But no one drowns here: as soon as we can walk and speak, everyone in the outlying Counties learns how to tell when the water table is rising and the ground under you can’t be trusted. I didn’t watch her die, unlike all the other inhabitants of Esopus Creek, their eyes trained on their tablet screens until they turned red and bloodshot—because how can you sleep, when you might risk missing the climax? The slaughter?

Her wet hair is all I can bear to look at. If I look at her face, or the utter stillness of her rib cage as it presses up against the fabric of the too-small dress—or, worst of all, the ring of bruises around her throat—I’ll have to duck under the counter and retch.

You wouldn’t imagine, in my line of work, that I’d have such a weak stomach.

Floris sets his jaw. “Is your brother here?”

My eyes narrow in response. I haven’t been hard enough on him. “Luka would tell you the same. No human corpses.”

I almost add another sorry, but if I do, he’ll ask for Luka again.

“I can pay more,” Floris says instead, voice pitching higher.

“Sixty-five credits.”

Buy the Book

Fable for the End of the World

Our rate for white-tailed deer is sixty, and with the way they’re dying off, soon we’ll be able to charge twice as much. I’m not going to butcher a dead twelve-year-old for two extra packs of peach-flavored decon-tabs, even if it would make Mom happy.

Besides, Floris is lying. He can’t pay more. If he had the credits, Sanne wouldn’t be dead. This fact makes it difficult to pity him. If he runs up even more debts, he’ll have nothing left to pay with but his own life. Sanne was a flimsy shield, thrown up between him and Caerus’s collectors. Their cruel vengeance, disguised as justice.

Floris’s lower lip quivers, and it makes the rest of his face look all the more gaunt and hollow. He’s from Upper Esopus, which means he eats better than we do, but not by much. Though I know it wasn’t food that racked up his debts. It never is.

I let my gaze slide down to Sanne again. Her eyes are half open, pale lashes like dandelions that could still be blown.

That’s one little thing I’ve learned in this job: It’s actually hard to get a dead person’s eyes to close. Everyone thinks that when you die, you become limp and pliable, when really, it’s the opposite. In death, the body seizes up. Rigor mortis. Eventually, of course, it rots away into nothing, but at first it stays stiff and still, as if trying to preserve itself as it was in the very last moment it was alive. In a way, it makes my work easier.

I always think of it like that—like the corpses are helping me as much as I’m helping them. We both want to stay alive, or however close we can get to it.

When that thought occurs to me, a stone lodges in my throat. Not for Floris, but for Sanne. Because maybe this is better than being buried in an unmarked grave and forgotten. And because maybe Floris deserves the constant reminder of what he did to her.

With a quiet, sharp inhale, I reach under the counter and pull open one of the drawers. Floris’s brows leap hopefully.

I take one of the small glass bottles and hold it out to him, with no small amount of reticence.

“This is a mixture of alum and borax,” I tell him. “They’re both desiccants—they draw the moisture out of the flesh and help it last longer. I can’t tell you exactly how—”

But Floris is already grabbing my hand and prying my fingers open. “Thank you, thank you.”

“Wait!” I manage, as he’s sliding the bottle into his pocket. “You have to get it under the skin and…”

I trail off, because in the end I still can’t bring myself to give him step-by-step instructions about how to butcher and stuff his dead daughter.

Floris reaches for Sanne again. A little bead of water drips down her temple, and I have to fight the urge to wipe it away.

“Inesa,” he says, “you’re one of the good ones.”

I’m not sure if he means one of the good residents of Lower Esopus, the ones who don’t complain when the denizens of Upper Esopus flood our houses six times a year by keeping the reservoir too high; or one of the good taxidermists, the ones who don’t charge for every stitch of thread or droplet of glycerin; or one of the good Soulises—maybe. With how much everyone in Esopus Creek hates Mom, that’s not a hard title to win.

Or maybe he means I’m one of the people who doesn’t judge him for what he’s done. For paying off his debts with his daughter’s life. But he would be wrong about that. I might hate him less for it than everyone else in our town, but it’s not something I can forgive. Or forget.

I set my jaw and give him the coldest look I can manage, pretending that I’m eight inches taller, as tall as Luka. “I want seventy-five credits.”

Floris doesn’t say a word as he takes out his Caerus card and presses it against my cracked tablet, doesn’t say a word as he sweeps his daughter’s body off the counter and carries her toward the door. He forces it open with his foot, its rusted hinges creaking. When the door slams shut after him, the little wooden SOULIS TAXIDERMY SHOP sign clatters like a cheap wind chime.

I lean forward on my elbows and put my head in my hands. I have to breathe hard into the silence for several minutes and squeeze my eyes shut, until I stop seeing Sanne’s face. When my heartbeat has steadied again, I sink down onto the floor behind the counter.

The desiccant I gave Floris was worth ninety credits, easy. Luka is going to kill me.

I find out quickly enough why Sanne was wet—it’s raining. It hasn’t rained in a couple of days (a small miracle, for Esopus Creek), so I have to dig my raft out of the clutter behind the counter. The sky is a dusky purple, striped with pink from the pollutants that are strong enough to slice through the heavy clouds. By the time I’ve finished closing up the shop, the water is knee-high and my jacket is soaked.

It’s one of those rough, fast storms that sweeps in with little warning, the kind that’s likely to raise the water table enough to lap at the legs of our couch. At home Luka is probably already laying down sandbags. I get on the raft and test the depth of the water with my pole—it’s right up to the nine-inch notch—then push off into the rain.

The water is sluicing down Main Street, a murky, churning brown, rushing from Upper Esopus to Lower Esopus. It’s after six now, so the evening commute has started, all the shop owners clambering onto their rafts and poling up toward their houses on higher ground. Across the flooded road, there’s Mrs. Prinslew, down on her hands and knees on the porch of her shop, stuffing rags beneath the doorframe. All four of her sons moved south to the City, and now she runs the black market goods store all by herself. Wiping rainwater off her wrinkled brow, she sits back on her heels and swivels her head around, catching my eye.

The question rises instinctually in my throat: Do you need some help? But a second, stronger instinct pushes it down. Here in the outlying Counties, the offer is not a kindness. Because no assistance comes without gratitude, and no gratitude comes without debt.

That’s what Caerus taught us—slowly, and then all at once— when the credits ran out and they came to collect.

The most I can give Mrs. Prinslew is a wave and a nod. She nods back, and I pole on.

At this hour, the punters are out in force, hawking fares from people who can’t pole on their own. The punters have real boats, narrow and sleek, with a little platform to stand on and even a small carved seat for their passengers. It’s fifteen credits for a ride to the residential district, ten if you live in the Shallows. On the rare occasions that Mom leaves the house, she always hires one. She says she doesn’t trust my arm.

The streets of Esopus Creek run horizontally across the hill like striations on a cliffside, and the divide between Upper Esopus and Lower Esopus is stark. The houses in Lower Esopus have flat tin roofs and rotten wooden siding, paint stripped off after so many storms. They’re held aloft over the hill by spindly cinder block columns, porches sagging precariously.

The houses in Upper Esopus are round and white like insect eggs, made of durable plastic that the rainwater rolls right off. They have sheet glass windows and covered porches that can fold and unfold, depending on the weather. They’re Caerus pod houses, airlifted from the City and dropped right down on the hillside.

Mom says they’re sterile and ugly. Luka says she’s overcompensating.

Our house is at the very end of Little Schoharie Lane, the lowest street of the Shallows. Our neighbors have a bit of pride because there used to be a school here, ages ago, before learning was all virtual. Everyone likes to claim that their house is on the property of the old school, but Luka and I don’t bother pretending our house has any sort of noble pedigree. I pole into the yard and hitch my raft to the foot of the stairs. Then I clamber up, boots sliding against the wet concrete, my hair drenched even under my hood.

There are sandbags on the floor and I can smell blood as soon as I step through the door. I shrug out of my soaked jacket and hang it on the hook beside Luka’s. Mine is green, turned black by the rainwater. Luka’s is black, turned blacker. Today’s kill must have been messy.

He’s sitting at the kitchen table, hair drying in stiff spikes. As soon as he sees me he says, “Did you board up the windows at the shop?”

“I never took them down from last storm,” I say, and offer a huff of laughter, thinking he might laugh back. “Didn’t see much of a point.”

Luka offers only a grim smile in return. He’s fiddling with his tablet, scrolling between a game app and a news app. We’re both dancing around our twin questions.

How much did you make today?

How many did you kill today?

I blurt out my question first. “How many?”

“Two rabbits and a white-tailed deer.” Luka’s response is immediate, because he knows he did well. I could have guessed as much from all the blood on his jacket. “I was going to take them down to the shop, but then the rain started.”

“I’ll take them tomorrow.” I swallow. “We should start up-charging for the deer. I had a City buyer in today who told me he wanted four mounted heads—four. I told him it could be a month.”

“Bucks with antlers?”

I nod. “I had him make a nonrefundable deposit. Two hundred credits.”

I was proud of my work today, until Floris Dekker. I never feel bad about being shameless with the City buyers. They come in wearing shining black boots and jewel-toned slickers, and when they take down their hoods, their faces and hair are dry. They’re always jovial, remarking on the quaintness of the shop, politely ignoring the dripping ceiling and the buckets half filled with stale water. They don’t blink or scowl when I list my exorbitant prices, and sometimes they even apologize to me when they have to press their Caerus card three or four times against my cracked tablet to get the transaction to go through.

They want stag heads for their “dining rooms” and “dens,” places I’ve only seen on TV. The stuffed rabbits decorate their kids’ bedrooms. The birds, which I mount to look as if they’re midflight, wings fully spread, breasts puffed out proudly, are gifts for their wives.

It’s the Outlier customers I feel sorry for, the ones who come from other towns in Catskill County or even as far as Adirondack County, the ones who can only afford the scrawniest, scruffiest rabbits or the tiny field mice we sell for twenty credits apiece. Taxidermies are a luxury, plain and simple. No one needs them. But there’s a logic to buying them that City folk would never understand. Because when you’re tabulating the entire worth of your life, a cheery decoration or an expensive bauble is more valuable than a bushel of half-rotted black-market apples.

At least, that’s the logic that runs Mom’s life. I can hear her shifting in her room now, her bedsprings creaking.

“Good,” Luka says slowly. “So… how much did you make?”

Copyright © 2025 by Ava Reid, Used with permission of HarperCollins Publishers.