For years, the U.S. public has been hearing that prescription opioid pain relievers are always and forever a bad thing—and that doctors and big pharma companies are supposedly responsible for an epidemic of addiction and drug overdose-related deaths. However, these assertions are outright lies. Both the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Veterans Administration know it.

The recent national opioid settlement is as bogus as a three-dollar bill—and its associated injunction, cooked up with the collusion of 30+ state attorneys general, is destroying patient lives and pharmacy businesses by creating entirely unjustified shortages of legitimately prescribed controlled substances (opioid analgesics and others).

One of the prevailing memes that has distorted and misdirected public health policy on pain management is the outright silly notion that any patient who uses prescription opioids is at immediate risk of addiction. A second meme is the idea that doctors prescribing to their patients have contributed in major ways to the rising death toll in drug overdose-related mortality.

Both memes are outright lies—and many of the people telling those lies are fully aware that they are.

Let’s take the first assertion. Multiple studies prove it is grossly untrue.

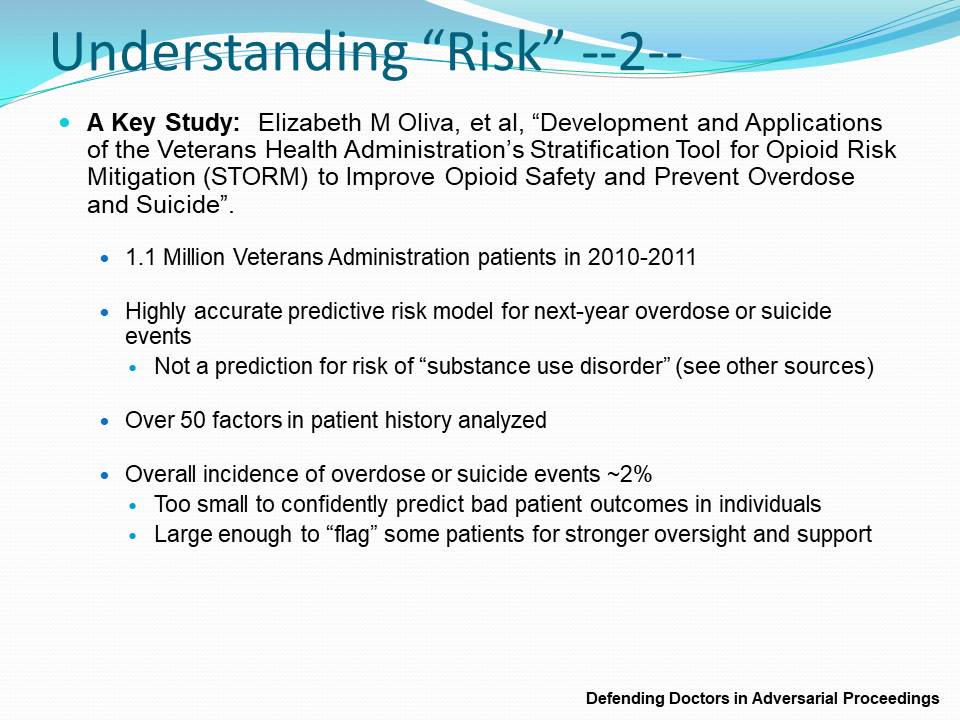

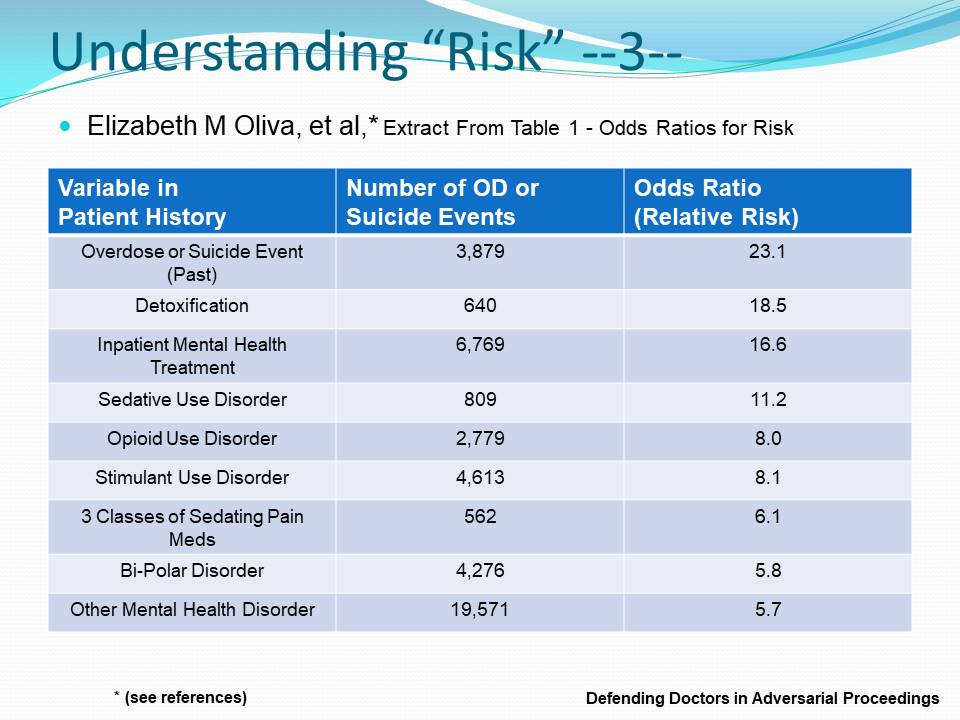

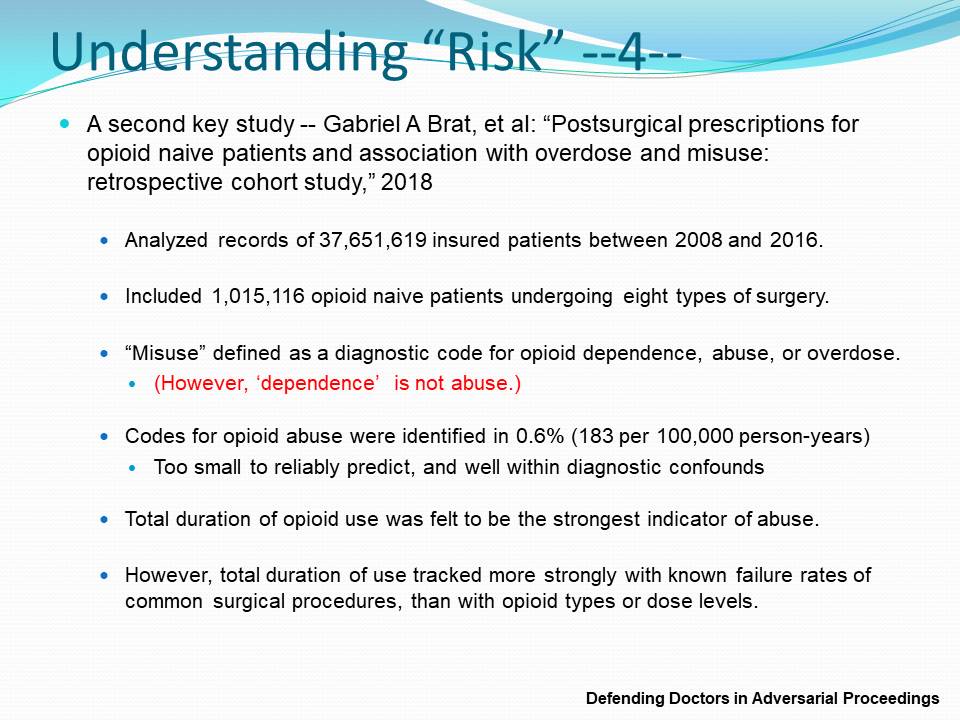

The outcomes of these studies are summarized in three charts below from a draft course in continuing legal education titled “Defending Doctors in Adversarial Proceedings,” soon to be published after accreditation.

Professor Oliva and her colleagues demonstrated that the risk of near-term opioid overdose or suicide events among VA patients who are managed on opioids is four to 23 times more significant from factors in the patient’s mental health history than from any aspect of opioid prescribing itself.

And now the second false meme.

Brat and his colleagues provided the largest multi-year study ever published on opioid abuse in opioid-naive patients treated with opioid pain relievers following surgery. When their error in defining opioid “dependence” as opioid “abuse” is accounted for, the net rate of real opioid abuse or overdose in this large population is significantly below one-half of one percent. And in view of the poor training of most doctors who diagnose abuse, the likely net rate of abuse is almost certainly below 0.2 to 0.3 percent (one patient in 500 records examined).

How many doctors do we know who can accurately predict which of 500 patients in their practices will become addicted to opioid pain relievers? Such statistics are within the range of confounds in medical practice.

Yet a third major false meme is also contradicted by published demographic data accumulated by the CDC and the National Bureau of Statistics. This is the false idea that prescription drugs are responsible for the majority (or even a reliably large portion) of all accidental drug overdose deaths. They aren’t. And nearly 40 years of U.S. drug mortality data reviewed by Hawry Jalal and his colleagues prove it:

As we observe from the figure above, from 1999 to 2016, prescription opioids are only one of eight factors in accidental drug overdose deaths. Prescriptions have never been reported by county coroners or medical examiners in more than 22 percent of cases. Unspecified narcotics or undetermined drugs appear in another 22 percent or so. CDC data reported more recently, with refined collection methods, reveal that prescription drugs are reported in less than 10 percent of all accidental drug overdose deaths—and a significant majority of drug overdoses involve both illegal opioids and stimulants like cocaine or methamphetamine, which almost never occur in medical patients.

Conclusions

From data published by the U.S. CDC itself, it is clear that doctors prescribing to their patients in pain are not now and have never been a significant cause of our U.S. opioid crisis. That distinction belongs to street drugs. Likewise, from the largest studies of outcomes from opioid prescribing, it is clear that addiction in medical patients is so rare that we cannot measure or predict it accurately. When drug overdose or suicide does occur among medical patients treated for pain, previous mental health issues are the dominant risk factors—not opioid prescribing.

There is no reasonable prospect of “solving” our U.S. opioid crisis by denying pain care to millions of U.S. citizens or persecuting hundreds more clinicians out of pain medicine or into prison. Present U.S. public health policy on the regulation of opioid analgesics and doctors who employ them is clearly fraudulent.

Richard A. Lawhern is a patient advocate.